Pittsburgh's housing authority is incentivizing landlords in more affluent neighborhoods to take housing vouchers.

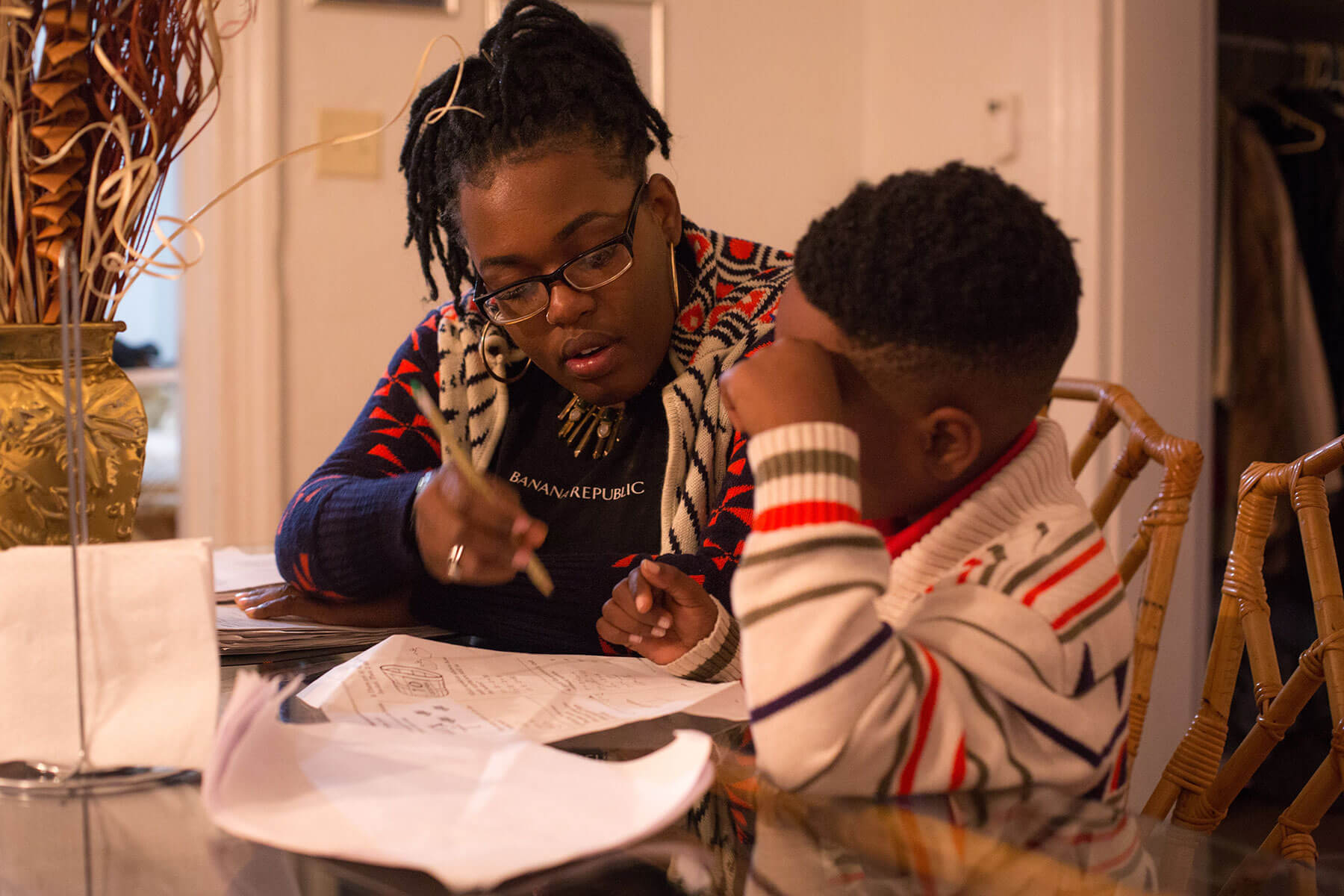

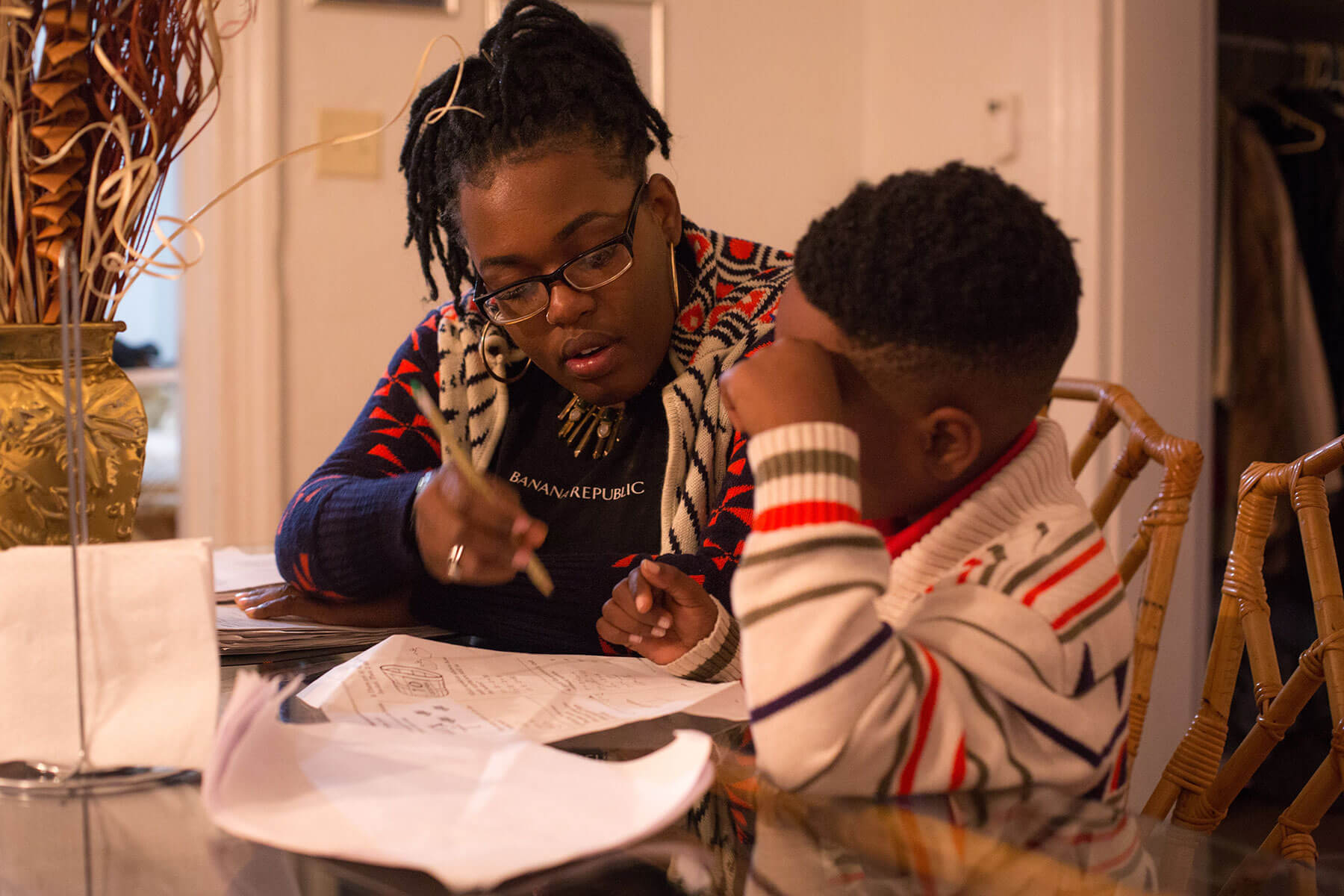

Matt PetrasFour years ago, Olivia Rash often worried about what the future held for her toddler son.

She found a two-bedroom apartment they could afford in county-run public housing in Braddock. But she was concerned about her son being exposed to drugs and violence and how that could impact him growing up.

“If your child wants to go outside or you yourself just want to go for a walk or something like that, you always have to be alert and you just never know when something could happen around you,” Rash said.

The solution, she said, was to move. The concept has been taken up by housing authorities in several U.S. cities, including in nearby Pittsburgh, where the housing authority in September launched a program intended to increase the use of housing vouchers in more affluent city neighborhoods like Shadyside and Squirrel Hill.

Rash said she might have benefited from a program like Pittsburgh’s, though she’s skeptical that overall living costs would be affordable in a pricier city neighborhood, even with subsidized rent.

At the time, she found housing on her own, first at an emergency shelter and then permanently in a three-bedroom, market-rate duplex in Munhall, a borough just outside of the city. She’s happy there, noting her proximity to healthy groceries at The Waterfront shopping complex. And she feels it’s a safer environment, so she’s not concerned about letting her son, now 6, play in the backyard.

“I don’t have to worry about if somebody going to try to run through my backyard because they just committed a crime or someone back there smoking weed,” Rash said.

According to The Opportunity Atlas, a data tool that examines economic outcomes by neighborhood for people born between 1978 and 1983, the median income for individuals who grew up in Braddock ranged from $22,000 to $27,000, compared to $32,000 to $40,000 for Munhall.

Could moving be an answer for other families? The question of how a neighborhood impacts long-term outcomes has been studied several times in recent decades. A groundbreaking 2016 study found children who were younger than age 13 when they moved from low-income neighborhoods to high-resource areas in several cities in the 1990s experienced better education and economic outcomes.

The research shows promise in finding long-term solutions to the harms of poverty. But it also raises questions about how lower-income residents are supported in their new environments, and, crucially, what happens to the neighborhoods they leave.

From the perspective of community leaders like Marimba Milliones, president and CEO of the Hill Community Development Corporation, providing funding for residents to live in higher-income neighborhoods is beneficial because it provides residents another option. But the key is that it doesn’t result in a lack of resources for neighborhoods that need them.

“I think it’s fine to allow people to have options to live wherever they feel is best for them and their family,” Milliones said. “Where it becomes problematic is when that is utilized as a method to disinvest from poor neighborhoods or withhold investment from neighborhoods that would otherwise be highly desirable.”

Increasing access to resources like groceries, transit and green spaces in low-income areas should not be deemphasized, she said.

“It’s really not an either-or,” Milliones said. “It’s a both-and.”

The Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh [HACP] said it is mindful of that concern.

In September, the authority began its initiative to increase payments to landlords in six higher-income neighborhoods. HACP’s goal is to give residents more choice in finding subsidized housing and increase landlord participation in Shadyside, Lower Lawrenceville, the Strip District, Southside Flats, Downtown and Squirrel Hill.

The housing authority worked with the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research when determining which areas to target for the initiative. Among the factors considered was access to resources like jobs and transit. Many of Pittsburgh’s lower-income neighborhoods are majority Black, while more affluent neighborhoods are majority white.

“You have better employment or more employment, you have better schools, better neighborhoods, better houses, better churches,” said HACP Housing Choice Voucher Program Director Marco Moo Young. “So all these different things enhance them and help them get into things that they weren’t able to get into.”

Chuck Rohrer, HACP’s communications manager, said the authority is trying to expand access, not reduce resources in neighborhoods in need.

“This is not replacing what we already do,” Rohrer said. “Our overarching goal is simply to create as many safe and accessible affordable housing opportunities as possible.”

Since Sept. 1, three units have been leased to tenants in the identified neighborhoods, HACP said in early December. “We've also received substantial interest from landlords and intend to promote the program to our clients and landlords throughout 2020,” Rohrer wrote by email.

Rohrer said HACP’s initiative is informed by research such as a 2019 Seattle study authored by a team including Raj Chetty of Harvard University. The researchers, in conjunction with the Seattle and King County housing authorities, looked at the impact of issuing housing choice vouchers for higher-income areas to 420 low-income and primarily single-parent families over the course of one year, starting in April 2018.

According to a survey conducted after the experiment, roughly 68% of families said they were “very satisfied” with their new neighborhood.

“Our experimental results imply that most low-income families do not have a strong preference to stay in low-opportunity areas; rather, barriers to moving to high-opportunity areas play a central role in explaining neighborhood choice and residential sorting patterns,” the researchers wrote.

This study follows the Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing project [MTO], a similar project with a larger scope conducted from 1994 to 1998 through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD]. The project tracked 4,600 low-income families, including a group given housing vouchers that could only be used in areas with less than 10% of the population living in poverty, a group with no geographic restrictions on their vouchers and a control group that did not move with vouchers but still received housing subsidies. The government chose residents in five major cities: Baltimore, Los Angeles, New York City, Boston and Chicago.

Participants felt “safer and more satisfied” with their new home neighborhoods and some saw improvements to their health, but, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the MTO program had no effect on children’s reading and math proficiency, the labor market and the use of social programs.

However, Chetty and others authored a study in 2016 that indicated children younger than 13 who moved as a part of the federal MTO project were more likely to go to college and make significantly more money. These children were also less likely to be single parents as adults, which implies more benefits could potentially be seen over time.

Still, economic outcomes for adults were again found to be largely unaffected. And teenagers saw slightly negative impacts after the move, such as an average $967 drop in expected adult yearly income. The researchers speculate this could be because moving disrupts teenagers lives by, for example, fracturing social relationships teenagers had formed in previous neighborhoods.

Longtime Northview Heights resident Marcus Reed, 47, is skeptical of the idea of incentivizing relocation. The community, which is predominantly Black and mostly composed of public housing, is one of the poorest in Pittsburgh. For Reed, it’s home.

“I know families been up there since the ’60s, since it started; it was built in 1955. You got families, I know, my cousin been up there before they even had concrete on the road, know what I mean?” Reed said.

He spoke with PublicSource hours before a Thanksgiving lunch held in his community. Gathering to eat some food with neighbors on a Saturday was a special occasion.

In his view, incentivizing relocation doesn’t do enough to address a broad affordable housing shortage.

“That wouldn’t make sense because there’s not enough affordable housing available now,” Reed said. “We’re 20,000 low-income houses short. The best way to help us in these communities is to help us make sure our councils are self-sufficient,” refering to the tenant council he leads as a volunteer.

Ann Sanders, public policy advocate for Just Harvest, finds the idea behind the Seattle study to be exciting, but she also voiced concerns.

In supporting the concept, she cited the mountain of evidence indicating a child’s ZIP code greatly determines their future chances of success. Sanders said the details of programs to increase mobility matter.

“Their kids are going to have better schools,” Sanders said. “It’ll probably be easier to get a job, but that assumes that that area has access to transportation, or, if they’re working evening hours, that they are able to have the same kind of support that they had in the community that they lived in before.”

Child care is also an important issue that must be considered in the policy discussion.

“Child care with evening hours is almost impossible unless you have a family member providing care,” Sanders said. “So if your family member doesn’t live in that community or somewhere where you can get to them easily, that’s going to obviously make it harder for you to move somewhere else because you need your whole support system to move with you as a parent.”

Another obstacle is the shortage of housing vouchers compared to the demand in Pittsburgh, Sanders said. HACP’s waiting list for vouchers is currently closed. As of Oct. 31, 8,684 families were waiting for vouchers.

“It’s not super helpful if your situation changes or you need to move or something like that, and there’s no affordable housing units, and you can’t get something to help you pay for rent,” Sanders said.

Robert Waters, 37, lives in Sheraden with his wife and four children, ranging in age from 18 months to 15 years old. He works full time in technical support for Verizon and spends an additional 20 to 30 hours of his week working on his photography business, Graffight Photography. His wife homeschools their children because they weren’t satisfied with the local school.

Waters has lived in both poor and rich neighborhoods and has seen the difference in resources firsthand.

“The teachers seem to be more invested, [and] they have more resources in more affluent areas because it’s all based on taxes and all of that,” Waters said. “Teachers want to be there as opposed to being placed there and not necessarily being there by choice.”

If finances weren’t an obstacle, Waters said they’d move. But he worries that living in a higher-income area would bring new financial hurdles, even if housing is made affordable.

“Will I be able to afford all the other things that it would take to live in that area? Will I be able to get to the places I need to go?” Waters said.

In Rash’s view, the overall costs of living in a more affluent neighborhood like Squirrel Hill could still be a barrier.

“It might be better...” she said. “But it would be harder just because when you move to those higher-income areas, they expect you to be able to afford the higher-income things.”

In Reed’s view, more money needs to be invested in lower-income communities. He volunteers as president of the Northview Heights Tenant Council, which he said received about $10,000 from HUD this year.

“That’s not enough to fight poverty. That’s just enough to throw a couple events and stuff,” Reed said.

His community knows the struggles of poverty. But Reed is quick to point out that residents like him want Northview Heights to improve, not to leave it behind.

“When you look past the negative part of it, people, they love the neighborhood,” Reed said. “We’re surviving.”

Correction (12/18/2019): This story originally misstated the number of families given vouchers in the Moving to Opportunity study.

Matt Petras is a freelance reporter based in the Pittsburgh area as well as a writing and journalism tutor for Point Park University. He can be reached at matt456p@gmail.com or on Twitter @mattApetras.

This story was fact-checked by Sierra Smith.

This project has been made possible with the support of The Grable Foundation.