(Photo illustration by Idil Gozde.

Original photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

(Photo illustration by Idil Gozde.

Original photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

What would make you stop eating meat? Is it the price? Maybe it’s knowing more about animal cruelty? Would you turn vegetarian, or at least reduce your meat intake, if the city you live in had a goal to battle climate change and said that eating less meat helps?

What would the city need to do to convince you?

The city’s most recent vegan festival was held in Franklin Park. (Photo by Oliver Morrison/PublicSource)

The city of Pittsburgh wants its residents to eat 50 percent less meat by 2030, according to a goal laid out in its climate action plan. Agriculture accounts for more than a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, and half of those emissions comes from livestock. Every bite of steak or lamb chops has a larger impact on the environment than a baked potato or bowl of rice.

But two recent attempts illustrate how challenging it may be to get people to cut back or cut out meat from their diets.

At the city’s most recent vegan festival in Franklin Park, a long line of people waited to buy food from Onion Maiden, a vegan restaurant. Lori Weber, who bought a vegan hot dog with kimchi and Korean mayo, became vegan last year because she wanted to eat healthier.

Health is often the most common reason vegans give in polls about what made them change. Like many vegans, climate change didn’t even factor into Weber’s decision.

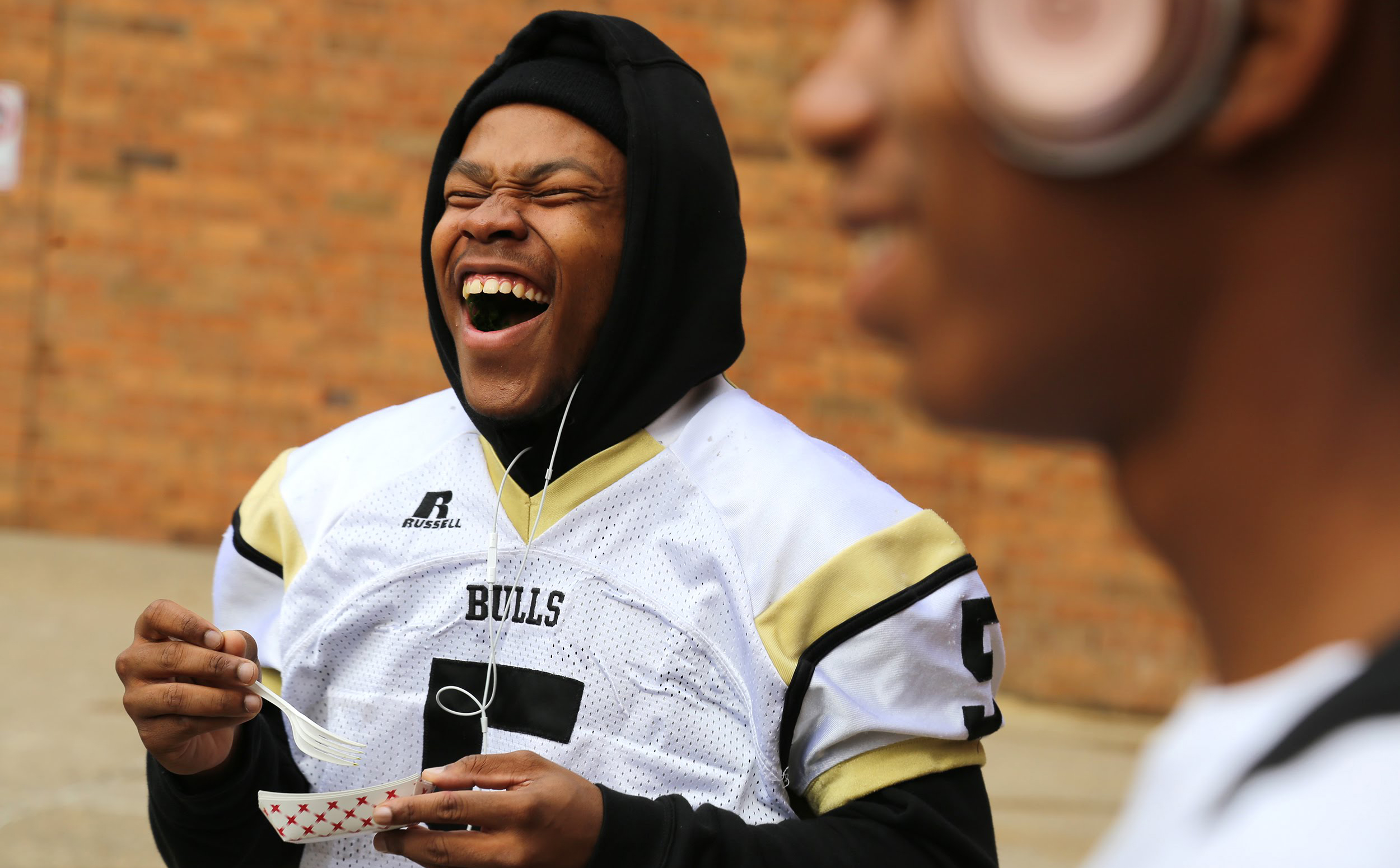

A week later, at Brashear High School 15 miles away, Adia Effiong of the nonprofit Grow Pittsburgh helped a handful of students make fresh salad from ingredients grown in the school garden.

Adia Effiong of Grow Pittsburgh asks three Brashear High School students if they want to taste the peas they harvested. Tymugyn Oaks (right) jokes about people calling him “Chef Ty” after he made a salad dressing by himself for the first time. (Photos by Oliver Morrison/PublicSource)

The idea is that students are more likely to eat vegetables they grow themselves and, if they are exposed to vegetables early, they are more likely to make them a part of their lives later on.

That was the theory anyway.

Terrance Triplett, who wore silver Beats headphones as he pulled up spinach leaves, worked diligently the whole period. But soon after he had washed, chopped and dressed the vegetables, he took a bite and melodramatically ran over to the garbage can to spit it out.

“It tastes like something sour in my mouth,” he proclaimed. “This is why I don’t try new things.”

Even if the kids liked the class, it was unclear whether this would ever translate into reducing how much meat they ate in 2030.

There isn’t much precedent for creating such a massive shift in how much meat people eat, even in the most vegetarian countries in the world, like India. But if the world is going to avoid overheating, cities like Pittsburgh may have to figure out how to reduce meat consumption.

Every time a cow burps, farts or poops, it releases greenhouse gases. After you add in all the grain it takes to feed them, the electricity for cooling their flesh and the fuel it takes to package, ship and cook, raising livestock produces about a sixth of the world’s greenhouse gases.

Although it’s even more inefficient in the developing world, the business of providing meat to consumers in the United States has a greater impact on emissions than construction, producing clothing, air travel or natural gas.

Not all meats are created equal. Every pound of beef produced is estimated to release about four times the greenhouses gases as a pound of chicken. It just so happens that the United States is one of the biggest consumers of beef, the gassiest of the meats besides lamb.

But Americans have cut back before. In 2014, Americans ate about 20 percent less beef than they did in 2005, not necessarily because they cared about the the environment, but because the price increased rapidly: Droughts and disease shrunk herds, and more countries started eating beef for dinner, causing a simultaneous shock in the supply and an increase in demand.

This cutback was, by one estimate, the equivalent of taking 39 million cars off the road. (Although, meat eating began to pick up again in 2015 as prices dropped.)

The temporary reduction, though, was a happy accident from an environmental perspective. The hope is that, if cities like Pittsburgh can start to be more intentional, it could aspire to the kinds of drastic reductions seen among smokers after the full force of the government programs, social pressures and market forces are unleashed.

Some Pittsburgh groups and institutions have been conducting experiments, many of which the city has drawn upon for how to change the city’s eating habits, such as creating urban gardens and buying more locally grown food. One of the most influential experiments has taken place in the University of Pittsburgh’s dining hall.

The University of Pittsburgh removed trays from its dining halls in 2009, and food waste fell by an estimated 40 percent. This fall, it shrunk the size of the plates in its main dining hall in half, hoping to reduce waste further.

Nick Goodfellow, the sustainability coordinator for the university’s dining services, has found that changing the environment in which people eat and the way food is presented may be more effective than trying to directly persuade people to eat less meat.

Nick Goodfellow serves as the sustainability coordinator for the University of Pittsburgh’s dining services. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

On Mondays, the cafeteria doesn’t serve any meat at its largest serving station. But it’s not touted as “meatless Monday.” They just don’t serve meat.

The city is proposing to create an Office of Food Initiatives with a manager who, like Goodfellow, would be in charge of coming up with new ways for the city to eat less meat and waste less food.

During a recent dinner at the university’s largest dining hall, freshman Chris Bizzoco grabbed a plate of pasta with roasted beet pesto, not because he cares about the environment or any labels.

“It’s just better,” said Bizzoco, who played lacrosse in high school and still has an athletic physique. Burgers and chicken fingers are unhealthy, he said.

The station where he picked up his pasta is the latest addition to the dining hall: the vegan station. But it’s not advertised as such. It just says “Taste of Pittsburgh” on the cart and only if you look closely will you see it labeled “vegan” on the menu.

Cook Leslie Jones serves lunch at the Magellan's station in the University of Pittsburgh's Market Central dining hall on Dec. 12, 2017. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

Goodfellow subscribes to a recent trend in branding vegan food as plant-based food, so students are reminded of the healthy produce they are getting rather than the meat they’re missing.

The main dining hall started serving vegan meals like sandwiches with roasted vegetables and eggplant in the spring at its own special station. The meals were popular enough that they decided to keep it full time.

Yet it was still the smallest, least popular food station, with around 300 portions served per meal. Goodfellow hopes that meatless options will eventually become more prevalent at all of the stations.

In December, the university adopted a goal of reducing animal-based foods by 25 percent by 2025.

The city has included in its climate plan some of the university’s strategies, such as trayless dining and smaller dining plates.

But there are only so many university dining halls and hospital cafeterias in which a benevolent food manager can trick people into eating in a healthier, climate-conscious manner. The city will have to adapt these lessons and find new ones for its drive-through lanes, microwavable dinners and tired parents calling for pizza.

Even if the city did drastically cut back on its meat consumption, it’s not clear that anyone would know it. There isn’t an agreed-upon way to measure how much meat the city eats.

The city draws on its relationships with utility companies to estimate greenhouse gases that are technically produced elsewhere but consumed in Pittsburgh. But it’s not clear whether big meat vendors in the region, like Giant Eagle, would voluntarily share their sales data.

A representative for Giant Eagle said the company does not share its sales information and wouldn’t “speculate on future meat consumption.”

Even if the city did build a coalition of meat purveyors, the greenhouse gases from meat consumption aren’t yet included in the city’s overall goal to limit emissions.

Whatever Pittsburgh produces counts against its own emissions. But whatever it imports, from other cities, states or countries, such as meat, doesn’t.

This “carbon loophole” happens in countries as well: one report suggests that, if the European Union took into account all the products, such as meat, that it imported from elsewhere, its emissions would have increased since 1990 rather than the 20 percent decrease it says it will achieve by 2020.

Some cities are looking to potentially include the climate impact of products people consume in future calculations.

But as of now, the city could end up touting its own reductions, while emissions at farms in Wisconsin or slaughterhouses in Kansas are increasing due to meat eaten in Pittsburgh.

This was the first time the city included a chapter on food emissions in its climate plan, and Grant Ervin, the city’s chief resilience officer, said the city’s most important short-term strategy will be improving the quality of its food data.

One of the country’s leading food economists recently told Vox that it often takes a long time for cultural changes to show up in people’s diets. News stories on saturated fat did impact the sale of eggs; it just took awhile.

So it’s possible that the city will eventually benefit from some of the cultural changes that are making it easier for people to eat less meat — like the meat-substitute market or the movement toward moderation by “flexitarians” who primarily eat vegetarian but occasionally eat meat.

Take Christina Padilla, a freshman at Carnegie Mellon University. She said she was looking for makeup and lifestyle tips on YouTube as a teenager, when she stumbled upon videos of vegans talking about cooking. She got hooked.

Her mom grew up on a farm in Peru raising animals, so Padilla thought she would understand when she stopped eating animal products.

“But it was the opposite,” she said. Her mom looked at Padilla’s rejection of meat as a rejection of her family’s cultural heritage.

She said it’s only been after years of explaining that her mom has come around to sometimes taking the chicken stock out of Padilla’s rice.

Story by Oliver Morrison

Fact-checked by Lindsay Patross

Edited by Halle Stockton and Mila Sanina

Illustrations by Idil Gözde

Design, development and cow methane illustration by Natasha Khan

Have additional questions or thoughts about this story? Email Oliver at oliver@publicsource.org or find him on Twitter @ORMorrison.

Who in the Pittsburgh region is making a unique or admirable effort to reduce their carbon footprint? How does the concern over climate change shape their everyday behavior? PublicSource is looking for nominations for Pittsburgh’s Climate BFF.

We will interview the greenest and most interesting nominees and feature short profiles. Email reporter Oliver Morrison at oliver@publicsource.org or call him at 412-515-0063 to share who you are nominating (it can be you!) and why the person deserves to be Pittsburgh’s Climate BFF.