(Photo illustration by Idil Gozde.

Original photo by Sarah Collins/PublicSource)

(Photo illustration by Idil Gozde.

Original photo by Sarah Collins/PublicSource)

The dozens of volunteers who showed up to plant trees along Bigelow Boulevard came for a lot of unexpected reasons.

Eric Chiu, a freshman at the University of Pittsburgh, needed volunteer hours to beef up his resume for medical school. J. Frank Dawson, the landscape architect who initiated the project, wanted Pittsburgh’s hillsides to explode with pink in the spring from the redbud trees. And Fadwa Brady, an Iraqi native, wanted to honor her recently deceased father who believed that life, like the 40 trees she wanted to plant in his honor, doesn’t end at death.

In just a few hours on this November morning, the group, many of whom said it was their first planting, had planted 36 trees.

(Left) Volunteers planted 36 trees along Bigelow Boulevard in November. (Right) Megan Palomo, the nursery manager at Tree Pittsburgh, at the organization's Lawrenceville location underneath the 62nd Street bridge. (Left photo by Oliver Morrison; right photo by Sarah Collins/PublicSource)

But a forester with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, who led the volunteer planting, privately explained later that it would have been faster and cheaper if none of the volunteers had even showed up and the conservancy had just done the work.

The real reason the volunteers were there wasn’t so much for their labor as their minds. They were being taught to notice trees.

“Trees are invisible,” explained Megan Palomo, who runs the nursery for the nonprofit Tree Pittsburgh, which provided small potted trees for each volunteer to take home. “They don’t see them at all. They just kind of feel the benefits that they provide. They can obviously tell the difference where there is asphalt with no shade versus sidewalk under a tree. One is miserable and one is very pleasant.”

In its recently proposed climate action plan, Pittsburgh committed to increasing its tree canopy about 50 percent by 2030. Right now, there are about 2.5 million trees in the city, more than most cities its size. The plan is to actively plant 780,000 more trees over 12 years, to increase the tree cover from about 40 percent to 60 percent.

While trees in parks and along highways may be the most visible effort, the real battle will be happening much closer to home: in front yards and backyards.

A lot of the city is already filled with buildings, roads or existing trees, where there isn’t any room for new ones. Yards are where most the open space remains. And so, from the perspective of the city’s climate goal, just as important as what the volunteers planted in the ground that day, were the seeds it planted in their minds.

To prevent the worst effects of climate change, we can’t just emit less of the gases we do now, according to a recent United Nations report. We will also likely have to pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to make up for our past sins.

But while scientists are experimenting with new technologies to remove carbon, they are expensive and unproven, according to the U.N. Trees, on the other hand, are cheap and reliable.

Forests could remove more than 5 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by 2030, according to the latest U.N. report released in November. That’s more than the projected improvements to cars, boats and planes combined and twice as much as all the projected improvements to buildings.

Along with renewable energy and more efficient appliances, the biggest projected reductions in emissions by 2030 will likely come from planting new trees and preserving existing ones. But planting trees is not a long-term strategy; it typically only works as more trees are added.

Although cities only take up about 2 percent of the world's land, they actually have greater potential than average to contribute.

A tree in the wilderness pulls carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, but a tree next to your house does that and also provides shade in the summer to lower your electric bill. It takes pollution out of the air to decrease your medical expenses. And soaks up groundwater to lower your sewer bill.

And tree planting is one of the easiest steps many people can take: Compared to buying an electric car or installing a solar panel, planting a tree is cheap. Baby trees can cost as little as a $1.

Pittsburgh already has one of the highest percentages of tree cover in the country among major cities and one of the most ambitious plans for increasing it.

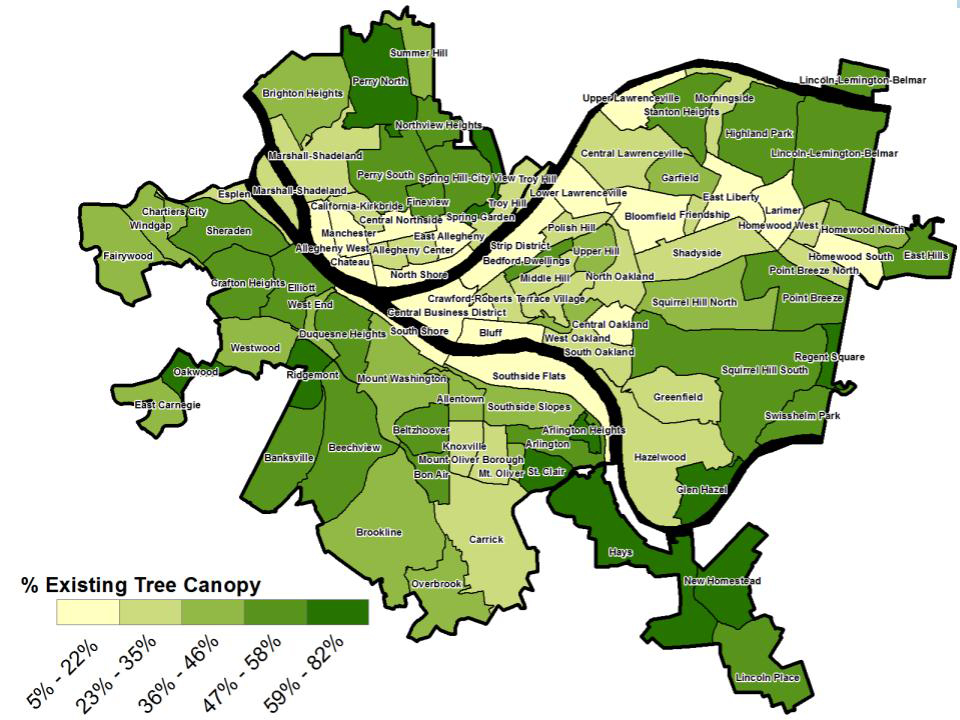

(Source: Pittsburgh Urban Forest Master Plan)

One of the city’s biggest advances in 2012, which was later copied by cities like Charlotte and Cleveland, was to create a detailed inventory and master plan for the future.

The city and its two tree-focused nonprofits have painstakingly catalogued all the trees along its streets, taken representative samples of trees across the city, and measured its total canopy from satellite images.

So now the city knows which neighborhoods have barely any tree cover (Chateau and North Shore) and which seven neighborhoods already exceed the city’s goal of 60 percent tree cover, such as Regent Square and New Homestead.

That’s how the city’s tree advocates know that, while there is some room left for adding trees in parking lots and along streets, the biggest spaces left are in people’s yards.

No one has done a full estimate of what it will cost for Pittsburgh to plant trees at the scale that is being proposed, and no new money has been allocated.

The trees planted in the park in November cost $185, plus another $250 to prepare the holes they were planted in. It costs $785 to plant a tree in a sidewalk.

The collective value of trees in Pittsburgh is greater than $1 billion, according to the master plan that has guided the city’s goals. The value is based on estimates of benefits like how shade can reduce electricity prices and how much water the trees prevent from entering the city’s sewage.

But this could understate their value, said Matthew Erb, the director of urban forestry at Tree Pittsburgh. “If all the trees disappeared, every pipe in the city would be at risk of failure due to the added stormwater,” he said.

Lisa Ceoffe, the city’s forester, said she’s limited by city codes in what she can do to protect the city’s tree endowment. Although the codes are relatively strong for the green hillsides, they don’t cover most of the flatter areas that have been attracting developers.

She said there is nothing saying that developers can’t clear-cut their land, and the codes don’t require a specific percentage of tree coverage. So even when there are requirements for replacing trees on hillsides or along streets, she said developers will sometimes replace old trees with fewer or smaller trees.

As a result of new developments (and a pest that has killed many of the city’s ash trees), Pittsburgh actually lost around 1,000 acres of tree cover, around 3 percent of its total canopy, between 2010 and 2015. Allegheny County lost 3,000 acres.

So Ceoffe is doubtful about reaching the city’s goal of 60 percent tree cover. “There is not a science, from what I understand, that pops out 60 percent. It’s basically a goal we’re trying to achieve” she said. “I think it’s a good goal. I don’t know how realistic it is.”

Joe Gregory, who helped create the plan for the Davey Resource Group, said he thinks 60 percent is still feasible and that the success of the plan so far shouldn’t be measured by tree coverage alone.

“It’s allowable to have some setbacks on your way to achieve the goal,” he said.

As the city tries to make space for potential economic drivers such as Amazon, trees may be sacrificed. Hays currently has the largest percentage of tree cover of any Pittsburgh neighborhood. The city recently set aside 89 out of 660 acres in Hays Woods for potential development. The rest of the Hays Woods land between the South Side and Homestead will become the city’s second largest park. The land would be perfectly positioned to house Amazon employees who commute across the river to work were Pittsburgh, and specifically the Hazelwood Green development, selected as Amazon’s location.

Grant Ervin, the city’s chief resilience officer, said the climate plan will be a tool for the zoning board and planning commission to ask developers questions about what the impact will be on the climate, including on the area’s trees.

So instead of a developer reaping profits from a property that took away value from the city’s trees, the city could push for changes to offset the damage to the city’s forest.

The city is depending on people like Ed Wrenn.

Wrenn has about 3,000 feet of yard space and only about 15 percent of it is covered by trees. He works long hours as a doctor and wants to limit his time in the yard. So he wants bushes and trees that will shield out the weeds.

But it’s a battle. His wife likes it how it is now. “We don’t see eye-to-eye with gardening,” he said. “She likes grass more than I do.”

Megan Palomo, the nursery manager for Tree Pittsburgh, helps Ed Wrenn select a tree for his yard at the Ginkgo Festival in November. (Photo by Oliver Morrison/PublicSource)

Wrenn’s wife isn’t alone. Many people prefer lawns over trees. Tree advocates not only have to try to change their minds, but also instill better tree planning. In the past, trees often interfered with utility lines, tore up sidewalks and caused injuries and damages during storms.

Wrenn showed up to the Ginkgo Festival in November to pick up some bushes and trees for his yard. The festival is Tree Pittsburgh’s attempt to celebrate the ginkgo tree, a tree so hardy it survived Hiroshima, Palomo said.

Wrenn bought a couple of paw paw trees. And then, on the spur of the moment, he bought a small cornelian cherry after Palomo explained to him how versatile it was.

“I hope we’ll be able to find compromise,” Wrenn said about the battle to add trees to his yard. “I hope I’m going to win completely in a way that makes [my wife] happy.”

On its face, Wrenn planting a few more trees wasn’t that big of a deal, but it was just the sort of win that Pittsburgh is hoping will happen more and more.

Planting trees is a short-term solution, a way to take some of the carbon out of the atmosphere until we figure out how to make our cars and buildings greener. If Pittsburgh did reach its goal of 60 percent canopy, its net reductions would fall to zero in a matter of decades. (Though they could still provide ancillary benefits, such as reducing energy use through shade.)

That’s because a tree releases its carbon back into the atmosphere when it dies and then decays. So it’s only while cities add additional trees and those trees grow to maturity, that the total carbon in the atmosphere declines. When the number of new and dying trees are about the same, the carbon being absorbed and the carbon being released cancel each other out.

The only way for trees to pull more carbon out of the atmosphere, at that point, would be to expand the goal again, to 70 percent tree cover or whatever the city decided was its absolute limit.

Then the city’s forest will go back to just being an urban forest, good for all the many reasons it's good for a city — shade, drainage, beauty, etc. — irrespective of the climate crisis that motivated its expansion.

Story by Oliver Morrison

Fact-checked by Abigail Lind

Edited by Halle Stockton and Mila Sanina

Illustrations by Idil Gözde

Design and development by Natasha Khan

Have additional questions or thoughts about this story? Email Oliver at oliver@publicsource.org or find him on Twitter @ORMorrison.

Who in the Pittsburgh region is making a unique or admirable effort to reduce their carbon footprint? How does the concern over climate change shape their everyday behavior? PublicSource is looking for nominations for Pittsburgh’s Climate BFF.

We will interview the greenest and most interesting nominees and feature short profiles. Email reporter Oliver Morrison at oliver@publicsource.org or call him at 412-515-0063 to share who you are nominating (it can be you!) and why the person deserves to be Pittsburgh’s Climate BFF.