February 20, 2020

376,000 PA drivers have their licenses suspended for unpaid traffic tickets. That’s more than the population of Pittsburgh.

By Juliette Rihl

February 20, 2020

By Juliette Rihl

February 20, 2020

By Juliette Rihl

Stories about how court fines and fees deepen poverty and entangle people in the legal system.

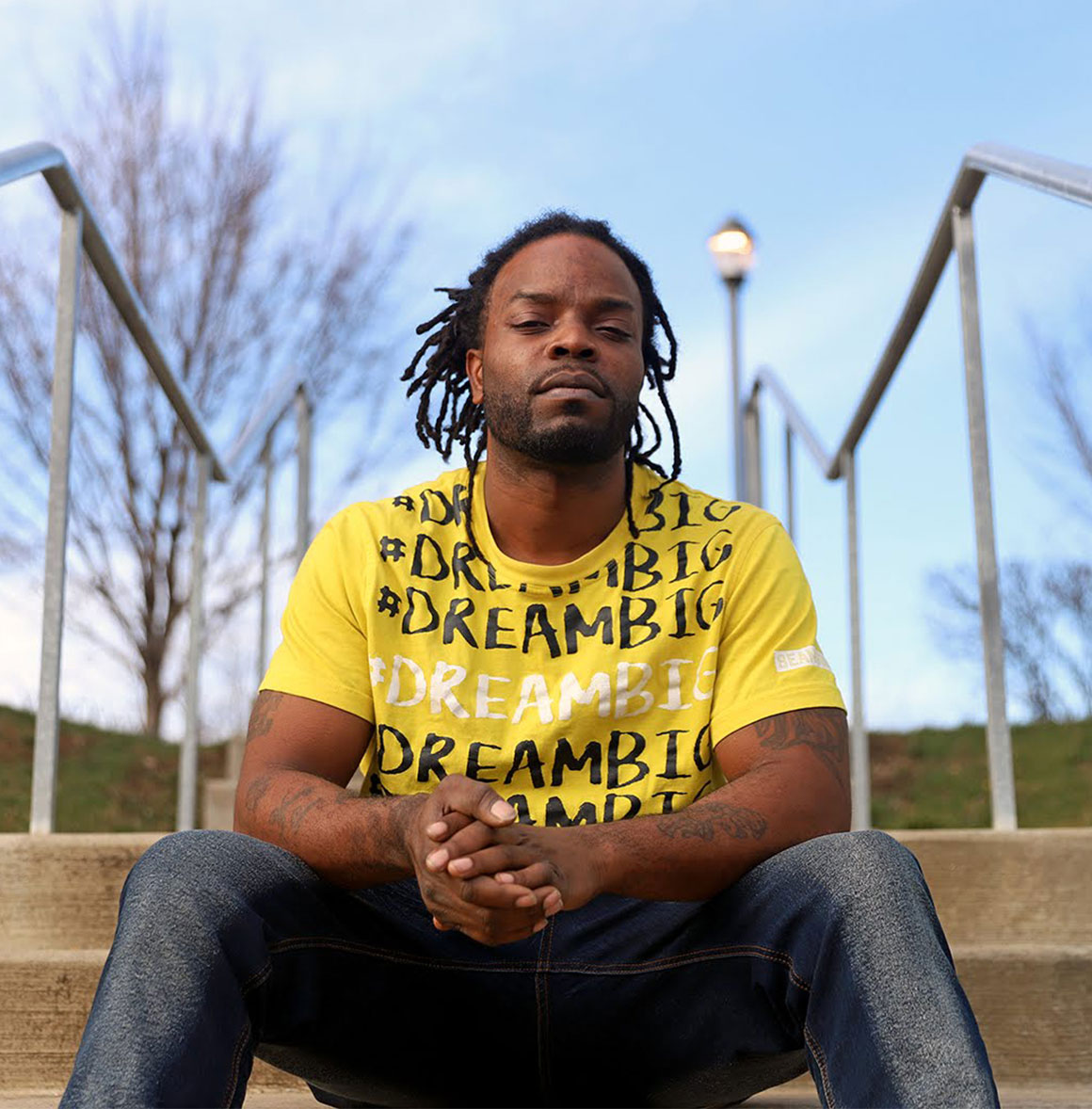

In December 2019, Derrick Macon Jr. was in Pittsburgh Municipal Traffic Court for one reason: to get his driver’s license back. It had been suspended since 2017 for not responding to citations for running a red light and driving without proof of insurance, both from 2016. The charges amounted to more than $650 in fines and fees, an amount Macon said he couldn’t pay.

In August 2017, a police officer pulled him over and told him his license was suspended. “I had no clue,” Macon said. The officer gave him a citation for driving on a suspended license.

For months afterward, 34-year-old Macon woke up at 4 a.m. to catch three buses from his home in Wilkinsburg to the warehouse in Robinson where he worked at the time. He said the trip took up to two hours. Losing his license had other repercussions. He had planned to obtain a commercial driver’s license and apply for higher-paying jobs as a truck driver. With his license suspended, he could no longer do so. “That messed me all up,” he said. “I was missing great jobs.”

Macon said he had his license restored in January. He started a payment plan though still has a court date for driving on a suspended license.

Derrick Macon Jr. outside of his home in East Hills. (Photo by Jay Manning/PublicSource)

The heart of the matter: In Pennsylvania, state law requires the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation [PennDOT] to automatically suspend a resident’s license for not paying or responding to a traffic citation — even for offenses that don’t otherwise warrant a suspension, like running a stop sign. According to PennDOT, 376,000 drivers — 29,000 in Allegheny County — have their license suspended for failure to pay or respond.

PublicSource spoke to eight people who have had their licenses suspended for failure to pay or failure to respond to a traffic citation. One 26-year-old single mom had her license suspended in 2018 for not completely paying off the fines and fees related to a 2012 DUI in Washington County. She said she has no other way of getting to work, so she continues to drive. She was caught driving on a suspended license three times last year, causing her to accrue more fines and fees and three years worth of additional suspensions.

For Macon and many others, the practice creates a catch-22: not paying one’s fines results in a suspended license, making it harder to work and pay the fines that caused the suspension.

A national issue: Forty-four states and Washington, D.C., suspend driver’s licenses for failure to pay, resulting in at least 11 million suspensions across the country, according to Free to Drive, a national campaign for license suspension reform. The campaign’s leaders believe the estimate is undercounting because there is no national standard for tracking suspensions.

What advocates are saying: Organizations across the political spectrum are pushing for reform.

“When you take away the driver’s license of someone who doesn’t have the ability to pay in the first place, they’re not suddenly going to be able to pay,” said Sam Brooke, deputy legal director of the Economic Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Southern Poverty Law Center is one of more than 100 bipartisan organizations that created the Free to Drive coalition in September 2019. “The idea on paper may sound right, but the consequences for those who really aren’t able to pay are quite severe.”

“We’ve got to find the right balance,” said American Conservative Union attorney David Safavian. “We’re not saying that people should not be held accountable … but suspending someone’s driver’s license for unpaid fines and fees is just one of the dumbest ideas I’ve ever heard. How do we expect them to get to work?”

What lawmakers are saying: In July 2019, Pennsylvania State Rep. Jake Wheatley, D-Hill District, introduced House Bill 80, which would create a one-year driver’s license amnesty program for people who have their license suspended for failure to pay or failure to respond to a traffic citation. The program would still require individuals to pay the fines, fees and penalties for the original offense but would provide amnesty from subsequent suspensions resulting from driving with a suspended license. The program would also allow for community service to satisfy the underlying charge.

State Rep. Mike Carroll, D-Luzerne, is the Democratic chair of the House Transportation Committee. He said the suspensions are the state’s way of forcing a person to settle their traffic charges. “If you run the stop sign and you can just ignore it without any consequence, I would suspect a lot of people would ignore it,” he said. Carroll supports House Bill 80.

State Rep. Todd Stephens, R-Montgomery, has hesitations about creating an amnesty program. “I worry that the message we would be sending would be that, if you go ahead and ignore the citations, someday they’ll just go away,” he said. “That being said, I think we need to find a way for people to get out of the perpetual cycle of suspensions so that they can be gainfully employed.” Stephens suggests considering the use of community service to pay off traffic violations or making it easier to obtain an occupational limited license.

What judges are saying: McKees Rocks Magisterial District Judge Bruce Boni said the threat of suspension is often effective in prompting people to pay. But for those who can’t, he called the practice counterproductive. “Unfortunately, for people who are financially stressed, you take away their license, and they can’t go to work,” he said.

Pittsburgh Magisterial District Judge Richard King said the law needs to be revamped so that those found guilty of an offense are still held accountable but can get to work. “What if there’s some young guy working in Pittsburgh at the cracker?” he said, referring to Shell’s ethane cracker plant being built in Beaver County. “You can’t take a bus to the cracker.”

Disproportionate impact: To a moderate degree, lower income communities tend to have a higher rate of license suspensions. A PublicSource analysis of PennDOT data and income data from the U.S. Census Bureau found a statistically significant relationship between the median income of Allegheny County ZIP codes and the percent of the population in that ZIP code with a suspended license for failure to pay or respond*.

In the three Allegheny County ZIP codes with the highest suspension rates — 15104, 15208 and 15110 — 8% of the population has a license suspension for failure to pay or respond. All three ZIP codes have median household incomes of under $36,000. The median area income for Allegheny County is $56,333.

According to research by the Buhl Foundation, license suspensions also disproportionately harm young people in Pennsylvania. In a 2019 study, the Pittsburgh-based foundation found that every year, 5% of 16- through 24-year-old Pennsylvania drivers have their licenses suspended. The most common reasons for license suspension were failure to pay (36%) and failure to respond (17%).

“It’s a vicious cycle. You need a license to get a job to pay a fine, but if you don’t have a license, you can’t get a job to pay the fine that you lost your license over,” said Fred Thieman, the Henry Buhl, Jr. Chair for Civic Leadership at the Buhl Foundation, who led the research. Thieman, who is not advocating for specific legislation, described the current system as "a backwards policy.”

A person can have their license suspended even before they have one: According to PennDOT, thousands of unlicensed drivers have their driving privilege suspended.

In the early 2000s, Tangerine McDaniel, a resident of Perry Hilltop in the North Side, was cited for having expired emissions stickers and driving without a license. She was unable to pay the fines and fees, so she ignored the citation. Despite not having a license, her driving privilege was suspended indefinitely.

Tangerine McDaniel drives her son Garrett Davis, 14, to Pittsburgh King PreK-8 on a recent Thursday morning. (Photo by Ryan Loew/PublicSource)

For a decade, 47-year-old McDaniel didn’t drive. She took public transportation, cabs or jitneys with her five children. Finally, in 2015, McDaniel went to Pittsburgh Municipal Traffic Court to settle the citations. The judge dismissed the case, lifting the suspension. Two years later, she passed her driver’s exam.

She called having her license a “life-changer.” Now, she drives her son to school and works with people with intellectual disabilities, a job that requires a license.

“I feel so liberated,” she said. “It’s convenient. I’m able to just walk outside and go to the store.”

*The analysis used PennDOT data from January 2020 showing the number of licenses currently suspended in each ZIP code in Allegheny County for failure to pay or failure to respond to a traffic citation. The data was compared to U.S. Census Bureau data of median income and population size for each ZIP code. A regression analysis of ZIP code median income and percent of population with suspended licenses for the reasons above produced a 0.6 r-value at 95% confidence. ZIP code data is imperfect because it can include portions of different neighborhoods with varying socioeconomic levels. Neighborhood-specific data was not available from PennDOT. Special thanks to Nick Cotter and to the Western Pennsylvania Regional Data Center for their help in analyzing the data for this story.

The next story in The True Cost of Court Debt series will explore how some people who can’t pay their court debt are put in jail. Check back on Feb. 27 or sign up for the PublicSource newsletter to make sure you don’t miss it.

Juliette Rihl is a reporter for PublicSource. Juliette is a Justice Reporting Fellow for the 2019 John Jay Fellowship on “Cash Register Justice.” She can be reached at juliette@publicsource.org.

Lead photo by PublicSource Visuals Producer Jay Manning.

This story was fact-checked by Matt Maielli.