February 6, 2020

Court fines and fees generate important revenue. But for some people, they’re an insurmountable hurdle.

By Juliette Rihl

February 6, 2020

Court fines and fees generate important revenue. But for some people, they’re an insurmountable hurdle.

By Juliette Rihl

A new PublicSource series

The true cost of court debt

Stories about how court fines and fees deepen poverty and entangle people in the legal system.

Maleah Hartnett sat in the lobby of the McKees Rocks District Courtroom, crying as her 21-year-old daughter carried a small pouch to the clerk’s counter. She emptied the money inside and counted it out — $16.50. It was the first installment of her mother’s payment plan for an outstanding $206 bill for two minor traffic citations from almost 15 years ago. “You’re taking people that have nothing and demanding that they pay something,” 45-year-old Hartnett said.

Hartnett, who’d just had a payment determination hearing for the 2005 citations, hadn’t realized the case was still active. Not until she was in court for a separate case in the fall, and a constable walked up to her with a 10-year-old warrant for her arrest related to the unpaid citations. He gave her two options: Pay the money, or go to jail.

Hartnett lives in public housing in McKees Rocks and receives food stamps. Because of health problems, she isn’t able to work and is in the process of applying for disability benefits. She has no income. “They want people to come up with money,” she said after the Dec. 18 hearing. “I have no money.”

Every week, dozens of payment determination hearings like Hartnett’s are held throughout Allegheny County for people with outstanding fines and fees on offenses ranging from serious crimes to traffic tickets.

Even for something as minor as running a red light or driving with expired inspection stickers, not paying off the citation can result in an arrest warrant, a suspended license and, in extreme cases, jail time.

Throughout the county, there is more than $350 million in unpaid court debt on roughly half a million cases dating back to 1970, according to the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts [AOPC]. The debt includes fines and fees left unpaid by people of all income levels.

“They want people to come up with money. I have no money.”

Revenue from fines and fees funds multiple levels of government, due in large part to lawmakers imposing court fees as an alternative to raising taxes.

State Sen. Lisa Baker, R-Luzerne, is the Republican chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee. According to Baker, there are two reasons the state has added costs and surcharges to the justice system for years. First, the belief that wrongdoers should contribute to the costs of running the legal system and supportive services. And second, the need to generate revenue outside of raising taxes. “This is one of many nontraditional means that have drawn support in enabling our state to provide necessary services and meet public expectations,” she wrote in an email to PublicSource.

The debt cycle

Over the past six months, PublicSource spoke to people throughout Allegheny County struggling to pay their court debt on a range of offenses.

One 33-year-old woman from South Side is slowly paying off four traffic tickets from 2009. She estimates she still owes $1,100.

Solution: When to waive

Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas judges can waive fines and fees. But the rules are less clear for Magisterial District Court judges [MDJs], who preside over the lower courts. Some judges believe they have the authority to waive fines and fees. Others don’t.

Allegheny County President Judge Kim Clark is considering creating a court order allowing MDJs to waive fines and fees and close out a case if someone is indigent, according to Angharad Stock, the deputy administrator of special courts for Allegheny County. It would only apply to traffic and summary offenses.

A 46-year-old man who lives in the East End said he owes more than $20,000 in fines and fees related to low-level drug offenses. He is in long-term recovery and is working toward a degree in social work. His last arrest was in 2014.

A 20-year-old University of Pittsburgh student had a warrant issued for his arrest after he ignored an August 2019 citation for driving a friend’s car that didn’t have valid registration or inspection. He is now on a monthly payment plan to settle the $250 charge.

Evans Moore, a Pittsburgh-based organizer for the criminal justice reform organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums [FAMM], said situations where people cannot pay their court debt are too common. “Folks’ lives are being stymied because they can’t pay their fines and fees,” he said. “You get caught in this never-ending cycle of the criminal justice system.”

In 2018, Pennsylvania courts collected $444 million in fines and fees, roughly $35 million of which came from Allegheny County. Even so, the state has some $3 billion in unpaid monies on the books.

While fines are monetary punishment for an offense, fees (also known as costs or surcharges) are administrative charges that counties and states impose as additional sources of revenue. Fees, which fund items ranging from the court’s computer system to emergency medical services, are not meant to be punitive. Yet for many offenses, the cost of fees outweighs the fine, in some cases many times over.

“You get caught in this never-ending cycle of the criminal justice system.”

Pittsburgh Magisterial District Judge Richard King said very few people are unable to pay their court costs; they choose not to. Courts can administer payment plans based on what a person is able to pay, sometimes as little as $5 a month.

“They usually always have an ability to pay like $5 a month or something, but they don’t want to do it,” said King whose jurisdiction includes neighborhoods such as Allentown, Beltzhoover and Knoxville.

Yet several judges, including King, agreed that the same cost can have a drastically different impact on different individuals. To people with means, paying $300 is only temporarily inconvenient, said Magisterial District Judge Bruce Boni of McKees Rocks. “But a $300 cost for someone who is virtually indigent can be catastrophic.”

Magisterial District Judge Bruce Boni of McKees Rocks. (Photo by Jay Manning/PublicSource)

Boni, who presided over Hartnett’s case, said he and other magisterial district judges in Allegheny County consider the severity of the offense, a person’s financial situation and the associated fees before imposing a fine. Fine and fee amounts are determined by state law. While fee amounts are set, certain fines have a range, giving judges some discretion.

“These fines are specifically and thoughtfully tailored to the individualized situation,” Boni said. “How do you turn a wrong done by somebody, potentially against a victim, into money? That’s not easy.”

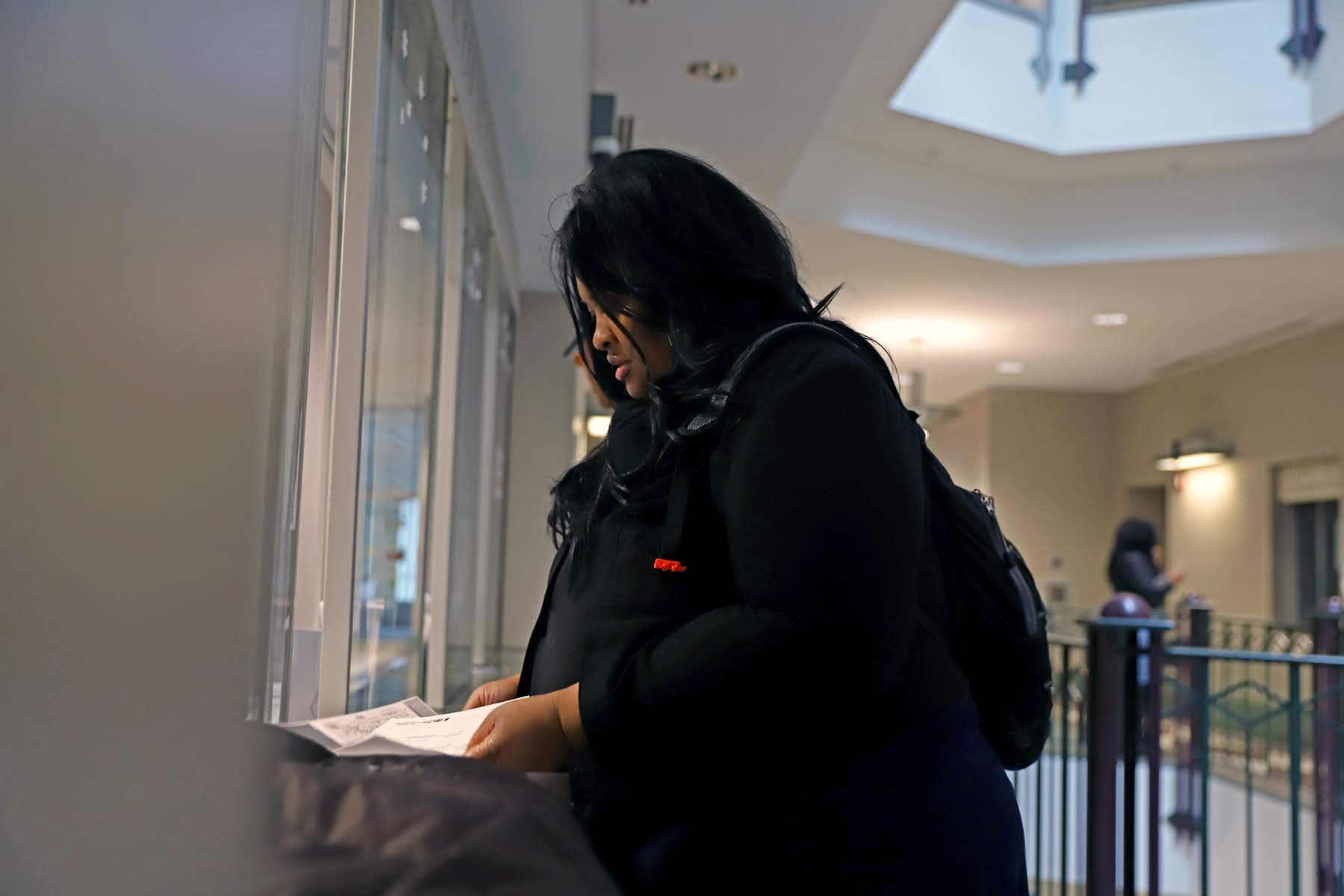

Adrianne Brown, a 48-year-old resident of Elliott in the West End, knows what it’s like to feel trapped by fines and fees. She sat in the back of Pittsburgh Municipal Traffic Court on a January morning, waiting nervously for her name to be called. Even though she’s been to court every month or so for the past year — either to make a payment or plead for more time — it still made her uneasy.

Brown is chipping away at the debt she owes for eight parking tickets and two moving violations — driving with an expired inspection and driving without insurance — all from more than a decade ago. She still owes about $1,600; she’s already paid roughly $400.

In the past, keeping up with the payments was a challenge, Brown said. Financial struggles, including experiencing homelessness at one point, caused her to fall behind. She feels a sense of urgency to pay off the moving violations in particular. Pursuant to Pennsylvania law, if a person misses a payment for a moving violation and doesn’t notify the court ahead of time, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation automatically suspends their license. The agency has suspended Brown’s license several times, making it harder for her to get to work and take her 10-year-old son to school in the East End.

Solution: Training judges

In February 2019, state Rep. Dan Miller, D-Mt. Lebanon, introduced House Bill 389 to train MDJs on what to do when a defendant does not pay. The training is intended to help judges evaluate a defendant’s ability to pay, consider alternatives to financial payment and offer payment plans. “We need to provide some sort of guide rails in how you are assigning costs and fines,” he said.

Finally, after almost two hours of waiting, she was summoned to the bench.

“How much you got?” Magisterial District Judge Robert Ravenstahl said. She was afraid he’d ask that. She could only pay $10 that day.

Explaining her situation, she asked to be put on a payment plan. “I would’ve put you on a payment plan last month, but I wanted you to bring money,” Ravenstahl told her.

Still, he agreed to give Brown a pair of payment plans requiring her to pay $50 total each month. At that rate, she’ll pay off her debt in about four years — more than 18 years since her first ticket. “I think I’ve put in enough time by now,” she said.

Pennsylvania organizations on both ends of the political spectrum are pushing for reform to fines and fees. “This is an issue that is really nonpartisan,” said Ashley Klingensmith, the state director of Americans for Prosperity-Pennsylvania. The nonprofit organization has partnered with other organizations of various ideologies, including FAMM, the ACLU of Pennsylvania and the American Conservative Union to advocate for criminal justice debt reform. “We’re seeing that people are choosing between paying fines and fees and putting food on the table,” she said.

Who should pay for government functions?

Court revenue funds multiple levels of government. That means if fine and fee revenue decreases, the government will have to make up for the money elsewhere — like by increasing taxes. Of the $444 million Pennsylvania courts collected in 2018, 54% went toward the state budget, 45% went to local governments and 1% went to fund things like airports, parking authorities and libraries. Fee revenue is expected to make up almost a quarter of the state court system’s $487 million budget for fiscal year 2019-2020.

State Rep. Tim Briggs, D-Montgomery, is the Democratic chair of the House Judiciary Committee. He said state lawmakers rely too heavily on fines and fees to fund functions that should be paid for by the state’s general fund. “But unfortunately, in a climate where we don’t want to raise taxes, fees become the substitute of taxes,” he said.

Baker has a different view. “To my knowledge, there have not been widespread complaints about this practice being patently unfair or completely lacking in discretion,” she wrote in an email to PublicSource. “Unless a court ruling would upend some aspect of this, it is hard to see support materializing for moving costs from those convicted of wrongdoing to taxpayers.”

While fines have been part of the criminal justice system for centuries, many fees have been added or increased in recent years, said Lisa Foster, a former judge and co-director of the national Fines and Fees Justice Center. According to Foster, fines and fees have risen dramatically in the past few decades. She credits the increase to two main factors: an increase in prosecution and incarceration rates, which drove up the cost of the legal system, coupled with legislators’ reluctance to raise taxes. “The justice system becomes a piggy bank,” she said. “This is a convenient way in the minds of many legislators for raising money.”

In some cases, using fines and fees as a revenue source has put pressure on police departments and judges to increase collections. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice found that the Ferguson, Missouri, police department was more focused on collecting revenue than ensuring public safety. The city anticipated 23% of its revenue coming from fines and fees that year, a proportion the department said “fundamentally compromised” the court. The collection practices, including what the Justice Department described as unconstitutional policing and unfair courts, disproportionately harmed Black people.

Solution: Factor in ability to pay

In San Francisco and Texas, fine and fee reforms have increased court revenue.

The Financial Justice Project in San Francisco led to millions of dollars of fines and fees debt being forgiven in the city and county. Since 2016, dozens of fines and fees have been eliminated, adjusted or discounted based on one’s ability to pay. The number of people paying their parking tickets has since quadrupled, and collections revenue has increased dramatically. The project later partnered with the Fines and Fees Justice Center and PolicyLink to create a national network called Cities and Counties for Fine and Fee Justice, which also provides grants to cities and counties working on reforms.

Under 2017 reforms, Texas judges must waive or reduce fines or fees in fine-only cases if a person isn’t able to pay in full. They must also allow the individual to set up a payment plan and offer community service, including vocational training or getting mental health treatment, as an alternative to payment. In 2018, court collections increased by about 7%.

Boni sees how a conflict of interest could potentially exist, but he said he doesn’t think it influences the decisions of his colleagues in Allegheny County. “In practice, I don’t see it as a problem,” he said.

State Rep. Dan Miller, D-Mt. Lebanon, is a former public defender. Like Briggs, he said the justice system should be funded by taxes, not by people in the court system. “In my opinion, you are eroding that trust and that sense of justice by putting that appearance of a conflict of interest, whether or not it is,” he said.

For residents like Hartnett, the lingering debt leaves her wondering what will happen if she can’t afford to pay. Her case has been dogging her for 15 years, and she’s still struggling.

By January, she had already fallen behind on her payment plan. Her daughter was able to make up for her missed payment — just days before another arrest warrant would have been issued. “Until those fines and costs are paid,” Hartnett said, “you’re not out of the clear.”

The next story in The True Cost of Court Debt series will delve into court fees — and how they can drastically outweigh the fines they accompany. Check back on Feb. 13 or sign up for the PublicSource newsletter to make sure you don’t miss it.

Juliette Rihl is a reporter for PublicSource. Juliette is a Justice Reporting Fellow for the 2019 John Jay Fellowship on “Cash Register Justice.” She can be reached at juliette@publicsource.org.

Photos by PublicSource Visuals Producer Jay Manning.

Design and development by PublicSource Interactives & Design Editor Natasha Vicens.

This story was fact-checked by Matt Maielli.