Solutions to gun violence must acknowledge racial inequities in our neighborhoods.

Essay by Nick CotterOn Oct. 27, 2018, I was eating breakfast with some friends at the Dor-Stop in Dormont when I saw on Facebook that there was an active shooter in Squirrel Hill North. Before the shooter killed 11 members of the Jewish congregation at Tree of Life, and before the world learned of his hateful, anti-Semitic and xenophobic motives, I immediately texted one of my best friends to make sure she was OK.

She is Jewish and goes to temple in Squirrel Hill. I cried in the middle of the diner when I learned that she wasn’t there and that she was physically safe.

Mass shootings are all too common in America, but this was the first time one had hit so close to home. The Tree of Life mass shooting awakened a public and political urgency around reducing gun violence in Pittsburgh that I had never seen before in my 30 years of living in this city. Thousands attended vigils, marches and protests; millions of dollars were raised for the victims, their families and first responders; and calls for local officials to do something about gun violence were heard by both the mayor and city council.

The frequency of mass shootings is unique to the United States. Though our country represents only 4.4% of the global population, Americans own 42% of the world’s guns. Among countries with more than 10 million people, only Yemen has a higher rate of mass shootings per 100 million people than the United States.

Despite these staggering statistics, mass shootings make up only a small fraction of U.S. gun-related deaths. Annually, suicides are the leading cause of death by gun in the United States, followed by lives lost due to urban gun violence and those killed by guns in domestic violence.

From October 2001 to October 2018, 520 people were killed in mass shootings in the United States, according to the book “Bleeding Out” by Harvard criminal justice scholar Thomas Abt. But during that same period, at least 100,000 people were killed in urban gun violence (fatal and non-fatal shootings that occur in the public spaces of cities and towns).

Both mass shootings and urban gun violence must receive the necessary public and political urgency to reduce them. However, I can’t help but feel that urban gun violence in the Pittsburgh region, and in the nation at large, does not receive the same public attention as mass shootings.

I’m not the only one: One 2016 survey showed 80% of Black respondents in the United States said gun violence was an extremely serious problem but 57% of Black respondents thought that most people in America don’t care about the gun violence that affects communities of color. Gun violence was also a primary concern of several long-term Black Pittsburghers I interviewed during my neighborhood walks for the Pittsburgh Neighborhood Project.

In a previous essay for PublicSource, I detailed the connection between race and concentrated poverty in Pittsburgh (and nationally), as well as the effects of concentrated poverty on child-to-adult outcomes. I stressed that while I grew up in a low-income, abusive home, I faced fewer obstacles in life on average than my Black peers because I grew up white in a low-poverty, low-violence neighborhood like Brookline.

What I did not detail in that essay were the specific community factors associated with concentrated poverty that often lead to negative outcomes for children as they grow into adults. Social science research suggests that childhood exposure to urban gun violence is the most important factor in this regard.

The cycle of violence is brutal, self-reinforcing and yet another perpetuator of poverty in our most disadvantaged communities. When violence is commonplace, schools cannot properly educate children who are in fear; parents keep their children inside out of fear for their safety; medical professionals cannot fully address the direct and indirect consequences of violence; enrichment activities suffer; and businesses and those residents who can leave flee.

Princeton sociologist Patrick Sharkey used quasi-experimental methods to show that children who took IQ tests within a week of a murder in their neighborhood scored a half a standard deviation lower than the average on IQ tests, all else being equal. These children aren’t less intelligent, but rather too preoccupied by fear caused by gun violence to learn and perform well in classrooms, as hypothesized by Sharkey. Other studies found that nearly one-third of Black women in poor, violent communities had PTSD. In "Great American City", Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson found that high homicide rates in neighborhoods predicted poor infant health. And so, the effects of violent crime loom large over the entire community, not just those who are direct victims of gun violence.

Gun violence does not affect city residents equally, by any measurement.

It is overwhelmingly concentrated in a small number of poor, segregated neighborhoods, carried out by a very small number of young men. The negative consequences also fall on residents who live in these neighborhoods long term, including residents with no link to the violence. Even within these neighborhoods, violent gun crime is disproportionately linked to just a few blocks.

Concentrated poverty is a common theme among those Pittsburgh neighborhoods that tend to have the highest homicide and non-fatal shooting rates in Pittsburgh per capita.

Of the top 20 neighborhoods with the highest homicide and non-fatal shooting rates per 500 residents in 2017, I found that 50% had poverty rates of 30% or more, and 75% had rates of at least 20% poverty or more.

The poverty rate is measured as the percentage of those living below 100% of the federal poverty level. Of the top-20 poorest neighborhoods in the city, 60% were also on the top-20 list of those with the highest rates of homicide and non-fatal shootings per capita. These statistics include homicides attributed to firearms and other means, though firearms make up the vast majority of cases.

Homewood South, Middle Hill and Fineview had poverty rates of at least 20% and were the top three neighborhoods with the highest homicide and non-fatal shootings per capita in 2017, according to data from the 2013-2017 American Community Survey [ACS] estimates and homicide and gun violence data via Allegheny County Analytics.[1]

Prominent sociologists and urban scholars have shown that gun-related crime is disproportionately higher in poor neighborhoods across the United States despite violent gun crime reaching historic lows in 2014. But concentrated poverty alone does not explain the entire story as to why particular neighborhoods have been persistently plagued by disproportionate rates of urban gun violence.

A growing body of research shows that racial segregation is one of the strongest predictors of urban gun violence.

This does not mean that violence is linked specifically to race, but rather to the consequences of segregation and disinvestment.

The nation’s most segregated cities, including St. Louis, Detroit and Baltimore, tend to also have the highest rates of violent crime per 100,000 people, even when the data is controlled for other variables like poverty, single motherhood, unemployment, incarceration, homeownership and education levels.

These same conclusions about segregation and violence hold true in Pittsburgh. Among the neighborhood-level variables I observed via 2017 ACS estimates, racial segregation was the most predictive measure of homicide and non-fatal shooting rates per 500 residents in Pittsburgh neighborhoods.

Like poverty, racial segregation is persistent over long stretches of time. While public perception tends to focus on the ways in which Pittsburgh is changing, racial segregation in most Pittsburgh neighborhoods is the same as it was nearly 30 years ago.[2]

Segregation in and of itself is not the primary antecedent of disproportionately high levels of violent crime.

Rather, as explained by Abt, racially segregated communities are often poor, disconnected from employment opportunities and do not share in the same institutional, political and investment capital as comparable white neighborhoods. Likewise, poor segregated neighborhoods are more likely to have high levels of distrust in the legal system, low levels of immigrant concentration and a small share of professional workers, the opposite of which are neighborhood factors that tend to reduce violent crime.

As renowned sociologist William Julius Wilson put forth in his seminal work “The Truly Disadvantaged,” poor Black people are often uniquely disadvantaged in that they are socially isolated from institutions, conventional norms and employment networks and reside in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty, unlike the bulk of poor white people who tend to reside in institutionally connected, low-poverty neighborhoods (at least in non-rural areas).

As further detailed by Abt and other researchers, our current patterns of neighborhood poverty, disadvantage and segregation are the result of decades of explicitly racist housing and lending policy in both the government and private sectors, economic restructuring and deindustrialization (which had a disparate impact on Black people), and white flight and outmigration.

The crack cocaine epidemic hit segregated, poor neighborhoods hard in the 1980s. As poverty and the prolonged lack of opportunity became a lasting reality for Black residents of the nation’s most segregated communities, some residents turned to available economic opportunity in the illegal drug market.

Gun violence today has less to do with disputes over drug turf than it did in the 1980s and 1990s, but some children are born into feuds that began decades ago. Others turn to violence as the result of significant exposure to trauma both inside and outside the home, according to Abt, Sharkey and other researchers.

Being Black does not increase the likelihood of involvement in gun violence. Instead, historic and current racism have ensured that low-income Black people are uniquely exposed to neighborhood-level factors that are associated with gun violence, which tends to be carried out by a very small subset of that population.

Those who live in our nation’s most segregated communities of color are the most at risk regarding exposure to urban gun violence.

Of Pittsburgh’s 90 neighborhoods, I found that 26 had no more than one homicide from the beginning of 2005 to August 2019. Nearly all of these 26 neighborhoods were lower poverty and nearly all of them have been majority white. Over that same time period, Homewood West, South and North, and the Middle Hill, each had 30 or more homicides. Of the 140 homicide victims from 2005 to August 2019 in these majority-Black neighborhoods, 137 were Black, and 118 of those 137 were killed by a gun.

While residents were undoubtedly exposed to significant trauma as the result of the Tree of Life massacre, it is the only instance of fatal gun violence from 2005 to August 2019 in the overwhelmingly white and affluent Squirrel Hill North; exposure to gun violence is a lasting reality for many of Pittsburgh’s poor and Black communities, not those in affluent white communities.[3]

From the beginning of 2005 to August 2019, 1,468 people were murdered in Allegheny County. Of that total, 77.5% of the victims were Black, and 89% of Black victims were killed by a gun. The county is only 13% Black as of 2018 estimates.

The City of Pittsburgh made up nearly half of all homicide victims in the county over this same time period; of the 669 homicide victims, 554 (83%) were Black, and 492 (89%) of these Black victims were killed by a gun. These numbers don’t include non-fatal shootings, which still inflict trauma on residents and their communities.

Nationally, homicide is not only the leading cause of death among Black men ages 15 to 34 but also accounts for more Black male lives lost than the other nine top causes of death among Black males combined.

In “Uneasy Peace,” Sharkey explored the years of potential life lost among homicide victims in different racial groups in 2014. The simple statistic is calculated by subtracting the age at which a homicide victim lost their life from the life expectancy for their given race and gender. The calculation is then summed over all homicide victims to give a sense of potential life lost.

This calculation was for 2014 — considered one of the least violent years in modern American history.

Males ages 15 to 24, who have been exposed to significant trauma and violence and have a history of violence, are the most likely to commit gun violence. Perpetrators of urban gun violence are also the most likely to be the victims of urban gun violence, as shown by Abt.

Gun violence also impacts innocent victims, including community bystanders who were not targeted but lost their lives for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In 2016, 6-year-old Isis Allen was killed on Zara Street in Knoxville, just a block over from my mom and grandma’s old house on Rochelle Street. Isis was unintentionally shot while on the front porch. The man who shot her was trying to intimidate someone who had threatened him.

Violence impacts children’s ability to see a future for themselves.

I see both the impact of violence on my own childhood and the relative advantages I had as a white male.

In high school, I missed 113.5 days of school. I was tardy 93 times, had countless detentions, scored a 470 on my SAT and graduated with a 2.07 GPA. To an outsider, teachers and even my guidance counselor, I was lazy, unmotivated and making poor life decisions. But my home life was emotionally and physically violent; my brother had cancer during that time; some of my classmates at school most commonly referred to me as “poor white trash;” and I didn’t yet comprehend that I could actually do better. I thought that at least when I skipped school to get extra hours at Giant Eagle, I was getting paid for it and my coworkers respected me.

My parents weren’t college graduates and none of us knew what sorts of things I would need to do to go to a four-year college (although my parents made a lot of sacrifices for me to go to Catholic school). I had severely limited evidence of success related to college and limited evidence of what an emotionally stable life looked like because of the frequent trauma I experienced at home.

My home life and inability to see any future for myself drastically impacted my decision-making. I didn’t care because there were few reasons to care. But I was lucky enough to receive incredible support and grow up in a low-poverty, low-crime neighborhood like Brookline, which eventually helped me turn my life around.

To make decisions for the long term, we need to actually believe we have a long term. That’s difficult to do when young Black men are dying around you or when Black lives have been cut short by the criminal justice system.

Too many young children who are Black and poor are exposed to a host of adverse factors in our most segregated and disadvantaged neighborhoods. Too many of them are repeatedly shown and told that Black lives don’t matter.

Besides some exposure to gun violence in Knoxville during my youth, my most significant exposure to urban gun violence came while living in Garfield.

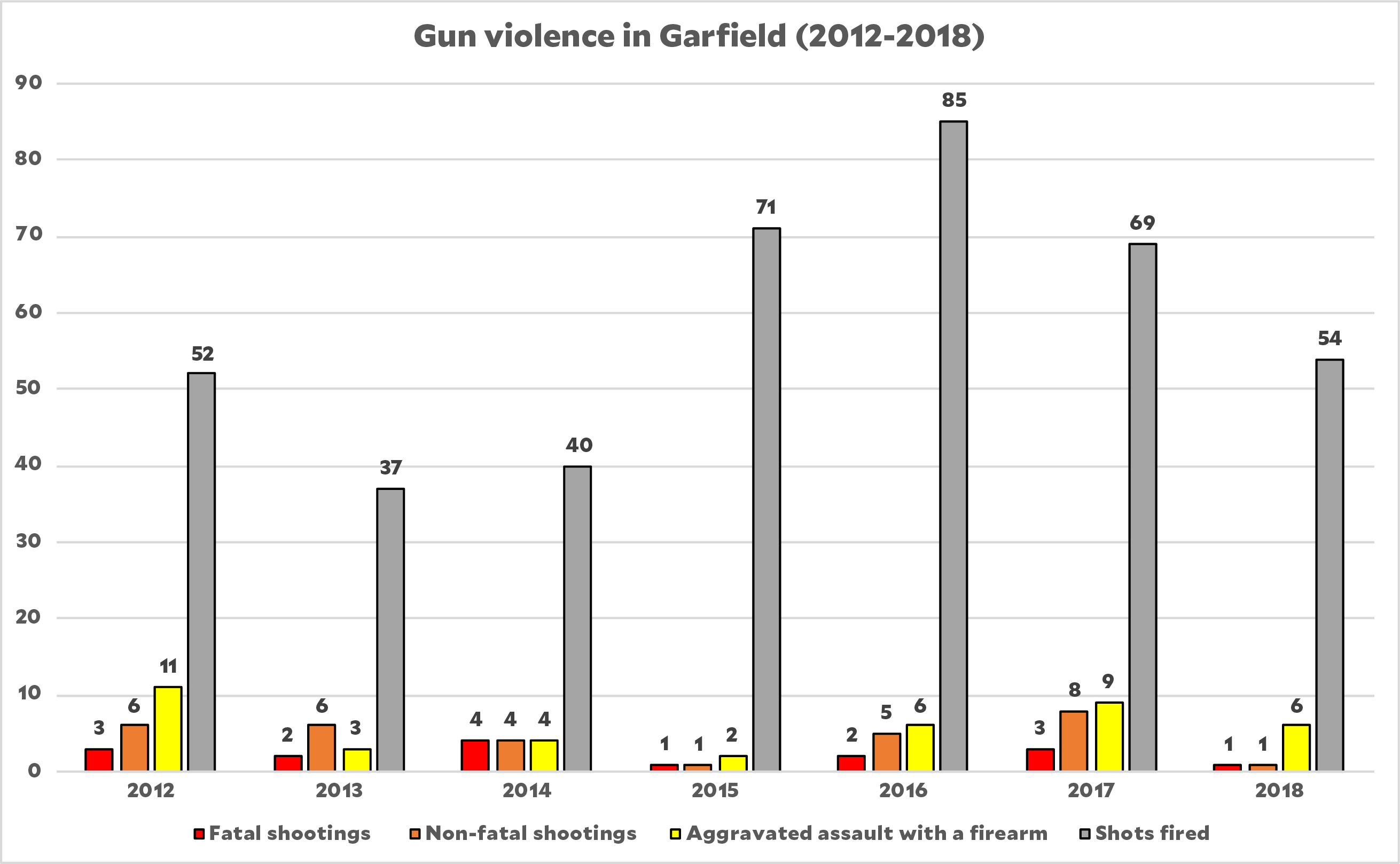

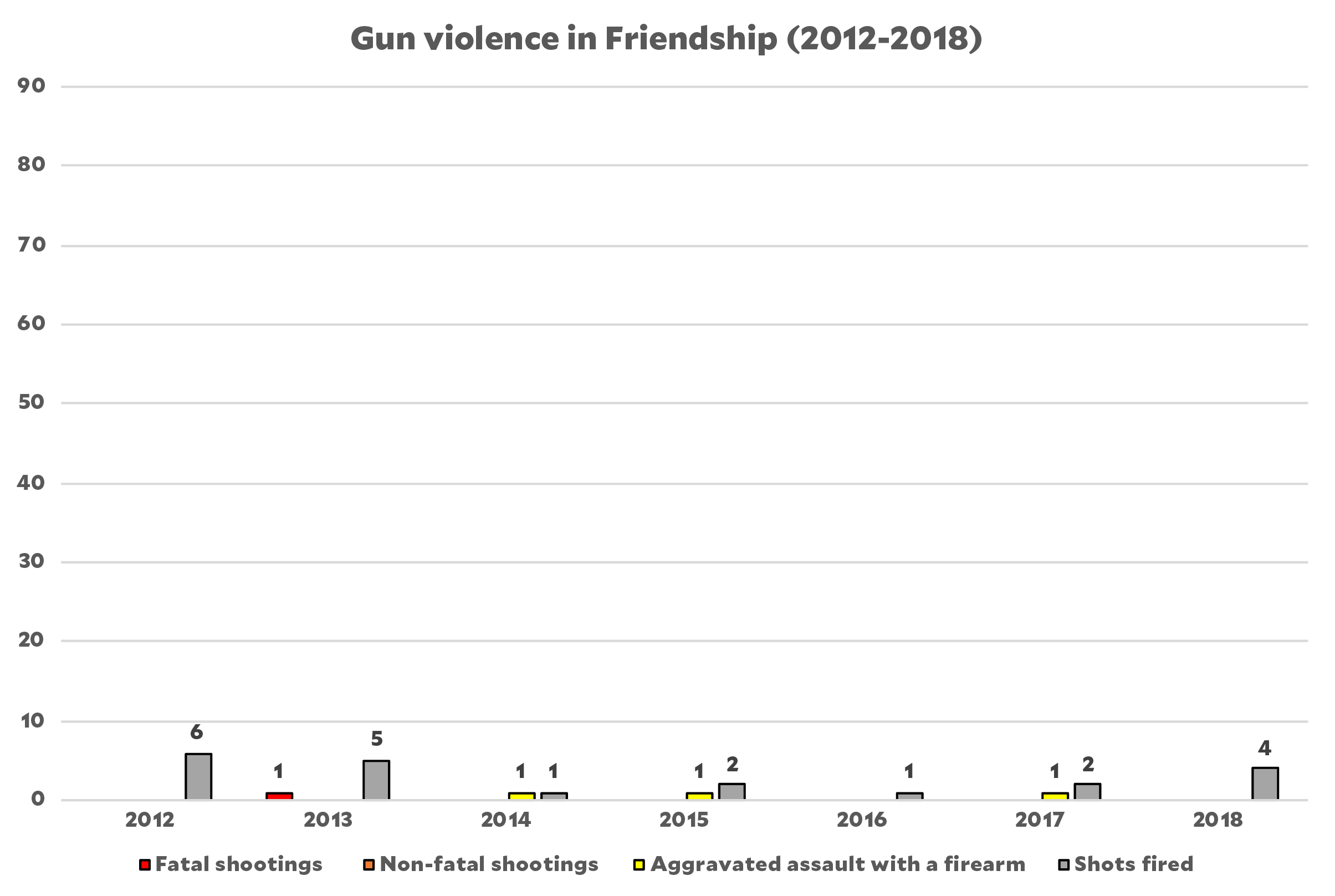

I lived in the neighborhood for about three years between 2014 and 2017. I treasured my time there. My roommates and I had fantastic neighbors. They didn’t mind my band practice. We had cookouts together from time to time, and the neighborhood is well connected to transit and amenities. But from the beginning of 2014 to the end of 2017, Garfield had 10 fatal shootings and 18 non-fatal shootings. By contrast, there were zero fatal or non-fatal shootings in Friendship during that time, an overwhelmingly white and affluent community only a short walk from our house on Broad Street.

Despite their proximity to one another, with one community sitting north of Penn Avenue and the other south, the difference in violent crime in high-poverty Garfield and lower-poverty Friendship is significant. According to my analysis, Garfield had the eighth-highest homicide and non-fatal shooting rate per 500 residents in 2017 of the 48 Pittsburgh neighborhoods and areas that had rates larger than zero. Friendship was one of 26 neighborhoods and areas that had zero homicides or non-fatal shootings in 2017.

While violence and shootings were relatively common during our time in Garfield, we weren’t affected like long-term residents, and I never felt unsafe. The shootings disproportionately impacted the Black community in the neighborhood.

We didn’t personally know the victims of gun violence and so didn’t mourn their deaths like a mother who mourns her lost son. We didn’t go to school in classrooms where bodies were missing from seats as a result of that gun violence. We didn’t go to the funerals of those who died, and we didn’t turn our heads every time we heard a strange noise while walking down the street.

For us, the level of violence in Garfield was unusual and tragic, but we were largely disconnected from it.

Urban violence rarely touches transient newcomers like us. But it deeply affects those who fall victim to it, their loved ones and children throughout the entire neighborhood. Children who grow up in Friendship grow up in a world that looks drastically different than the world children in Garfield grow up in, and yet they sit directly across from one another.

Nick Cotter is a researcher with Allegheny County and the creator of the Pittsburgh Neighborhood Project. He can be reached at pittsburghneighborhoodproject@gmail.com. The views expressed in this piece are those of the author alone. This piece does not reflect official views of the Allegheny County Department of Human Services. You can follow the Pittsburgh Neighborhood Project on Twitter @ThePittsburghNP.

This story was fact-checked by Juliette Rihl.

This project has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation.

1. Census tracts were aggregated to the neighborhood level using American Community Survey 5-year estimates for the years 2013- 2017. Percent living below the federal poverty line was examined. 911 data came from Allegheny Analytics. Fatal and non-fatal gun violent rates were calculated per 500 residents for each Pittsburgh neighborhood and neighborhood area. Neighborhood areas are those Pittsburgh neighborhoods that share a census tract with another neighborhood as of the 2010 census. Chateau, South Shore and St. Clair Village were left out of this analysis because they have populations of less than 100. Poverty rates were adjusted in student heavy areas by using rates for those 25 and up. ACS estimates can have considerable margin of error and this may impact results.

2. Census tracts were aggregated to the neighborhood level using American Community Survey 5-year estimates for the years 2013- 2017. Racial data for 1990 was gathered via the National Historic Geographic Information systems; census tracts in 1990 were aggregated to the neighborhood level. Chateau and South Shore were left out of the analysis because they had populations of less than 100 in both 1990 and 2017. Simple linear regression analysis showed that segregation (percent Black) had the strongest observed relationship with non-fatal and fatal crime per 500 residents for City of Pittsburgh neighborhoods and neighborhood areas; the relationship was moderately strong (R = .61, p < .01). All other observed neighborhood level variables (single motherhood, poverty, unemployment and income) had a moderate to weak relationship with fatal and non-fatal crime per 500 residents; meaning that R was .5 or lower. Relationship between percent Black in 1990 and 2017 was very strong (R = .84 with St. Clair included and R = .88 with St Clair Excluded, p < .01). ACS estimates can have considerable margin of error and this may impact results. 1990 census data from: IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota.

3. Homicide numbers and demographics from 2005 to August 2019 were gathered by neighborhood via the Pittsburgh Post Gazette's interactive homicide map. Point Breeze North was the only neighborhood that has teetered between majority Black and white over this time period, is lower poverty and had no homicides.