Students see new translation services and quicker transitions to regular classrooms. But they still face challenges.

Mary NiederbergerOn her first day at Brashear High School, Shahid Alowemer, a refugee student from Syria, stood alone in a cafeteria corner quietly eating an apple she brought from home.

“When I went to lunch, I didn’t know anyone. No one,” Shahid said.

Petite, painfully shy and with limited English language skills, Shahid watched the chaos typical of American school cafeterias: Noise echoed off of the walls as hungry students lined up for lunch, then gathered at tables where they ate and socialized, sometimes boisterously.

In Syria, and later in Jordan where Shahid’s family lived before coming to the United States, students packed food from home and ate it in class.

That cafeteria scene in August 2016 illustrated just how overwhelmed Shahid, then a junior, felt at her new school. She didn’t understand the language and habits of her American classmates, and the anxiety made her question if she would be able to succeed in a new education system.

But over the next two years, Shahid would become more fluent and confident in her English. She’d move from her English as a Second Language [ESL] classroom into classes with her American counterparts. Along the way, she found friends among Brashear’s ever-growing immigrant population and help from kind teachers.

“The teachers were really helpful even if I don’t understand them,” said Shahid, 19, now a student at Community College of Allegheny County. “They said if you don’t understand, come and ask us and we will help you.”

Brashear is a crossroads of languages, cultures and apparel from around the globe. ESL students comprise about a quarter of its enrollment. With around 300 ESL students, the population is the largest in the district.

But as the international population grows in Pittsburgh Public Schools, the district has struggled at times to best meet the needs of students in ways that help them and their families to navigate the system and improve their academic achievement and feeling of well-being and acceptance in their new surroundings.

Until recently, the district lacked sufficient translation services to ensure that all families received written and oral communication in their native languages.

And, until this year, some students remained in ESL classrooms for long periods of time, making it difficult to transition to mainstream classes.

Jonathan Covel, ESL director for the district, notes the importance of transitioning students when it is beneficial to their education.

“How do we do that in a reasonable time?” Covel said. “We don’t want to hold them back, and we also don’t want to push them into the pool when they are not ready.”

In the classroom, Pittsburgh’s ESL students often struggle to catch up. They face language barriers and sometimes have a history of interrupted or insufficient education.

At Brashear, 12.3 percent of ESL students scored proficient on state tests in English, 14.3 percent in math and 5.5 percent in biology in the 2017-18 school year. In the “all student” group, 46.5 percent scored proficient in English, 32.7 percent in math and 23.7 percent in biology.

In the most recent school year, the district moved more students out of sheltered ESL classrooms and into regular classrooms for subjects such as math, science, social studies and English. Both the Pennsylvania Department of Education and the Council of Great City Schools recommended the change.

The move is aimed at exposing students to the academic rigor of regular core content and improving students English language skills through immersion. Pittsburgh is following the lead of other large urban districts that have already made the change, Covel said.

Overall enrollment in Pittsburgh schools is leveling off after several years of decline. But the ESL population is one of the fastest-growing students groups, increasing by about 85 percent since 2007, Covel said. The district currently has about 1,200 ESL students. Most of them attend one of 12 schools designated as ESL centers.

Pittsburgh’s ESL growth follows a national trend. Across the United States, about 4.9 million students — or 9.6 percent — were English language learners as of the fall of 2016, according to the most recent data available from the National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. That compares to the fall of 2000 when 3.8 million students — or 8.1 percent — were English language learners.

Across Pennsylvania, about 68,000 students — 3.8 percent — were English language learners in 2018-19, according to Pennsylvania Department of Education statistics.

The move from the shelter of ESL classrooms presents challenges to Pittsburgh students who feel isolated from American peers.

Ikram Mohammed, 21, spent time in a refugee camp in Yemen before her family arrived in Pittsburgh in the winter of 2015. When she came to Brashear, she had to start in ninth grade because she did not have a certificate from Yemen to show she had attended high school. She graduated June 8.

In classes with American peers, she said she stayed quiet out of fear she’d be ridiculed.

“In American classes I don’t talk. I don’t say something. I just stay quiet,” Ikram said.

In the sheltered ESL classes, Ikram said students bonded together. They spoke different languages but shared common experiences as refugees and immigrants. And they weren’t afraid to make mistakes in front of each other.

“There is a perceived safety (in ESL classes) in being able to make a mistake. Hopefully we can do a better job of giving the kids the sense of freedom to make those mistakes,” Covel said.

Ikram acknowledged opening up over time. “I talk more. I have more American friends,” she said, noting the benefit of playing soccer for Brashear.

For the immigrant students, seeing a kind and familiar face is often a relief. Shahid remembers the day she met Ikram, who walked up to her with the Arabic greeting “As-Salaam-Alaikum,” which means “peace be unto you.” The two became best friends.

Shahid and Ikram both live in Northview Heights, a public housing plan operated by the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh. About 120 refugee families live there.

They said their residences there are far more clean and comfortable than the refugee camps where their families lived in tents before coming to the United States.

Shahid too remembers her hesitation to speak in front of American students. But being in mixed classes prepared her for attending CCAC. She made the dean’s list her first semester.

Shahid came a long way from the early confusion she felt at Brashear.

She remembers how she had difficulty mastering transportation, which included a Port Authority bus, the T and a school bus. And even finding the right class number was a challenge.

She recalled one room number that was in the 200s.

“How do I find it? I started at 100 and kept going,” she said. “Later I knew that 200 was something on the second floor.”

Sometimes she and other ESL students were late to class because of their confusion. But because of limited English skills they could not explain it to teachers. The language barrier sometimes resulted in detention.

Covel said each ESL student’s experience is different, based on personality, support in the family and community, personal experiences and previous schooling.

Two of Shahid’s brothers attended Brashear this year. She said they had had an easier time assimilating into regular classrooms and activities.

Her youngest brother, Yousef, 11, moved out of ESL classes after just one year at Arsenal PreK-5 in the 2016-17 school year.

In the beginning he didn't make a lot of American friends, but “now it is better,” Yousef said.

Being an immigrant at Arsenal is not an anomaly. According to data reported to the state, about 38 percent of 266 students at Arsenal in the 2016-17 school year were ESL students.

In Pittsburgh schools, 95 different languages are spoken by ESL students from pre-K through high school, according to Covel. Most common are Spanish, Nepali, Swahili and Arabic. The district gets up to 50 translation requests per day, Covel said.

But, in recent years, the district struggled to keep up.

Hoping to improve translation services, the Education Law Center intervened in the fall of 2015 on behalf of an ESL student who was also a special education student. The student’s parents weren’t receiving information about his individualized education plan in their native language, and the student was being assessed for services in English rather than his native language, according to Jackie Perlow, a staff attorney at the center.

As a result, a working group of representatives from the law center and the school district was formed in fall of 2016. They met for a year and created recommendations for best practices for ESL students.

Related: As Allegheny County's international student population increases, some districts feel a cost strain for ESL educationCommunication issues weren’t limited to special education. The district wasn’t sending basic information to families in their native languages, including information on weather closures and disciplinary issues.

“Families were not getting even basic things communicated to them,” Perlow said. “If schools were closing because of snow, if it wasn’t provided in their language, they didn’t know.”

It wasn’t the first time the law center intervened on behalf of ESL students. In 2005, the center filed a complaint on behalf of Somali Bantu students with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. According to the complaint, parents were not receiving appropriate translation services.

Among related changes made by the district:

For the translation services, the district uses the vendors Global Wordsmiths and TransPerfect, Covel said, along with freelance interpreters.

Perlow said she believes the district is “moving in the right direction” on the issue.

“There’s more work to be done,” she wrote in an email, “but we’re excited and proud of the positive steps the District is taking.”

At Brashear the staff is using a team teaching model to try to move ESL students to regular classes more quickly. ESL teachers work in the same classroom as regular education teachers for English and work as advisors for teachers in other core subjects.

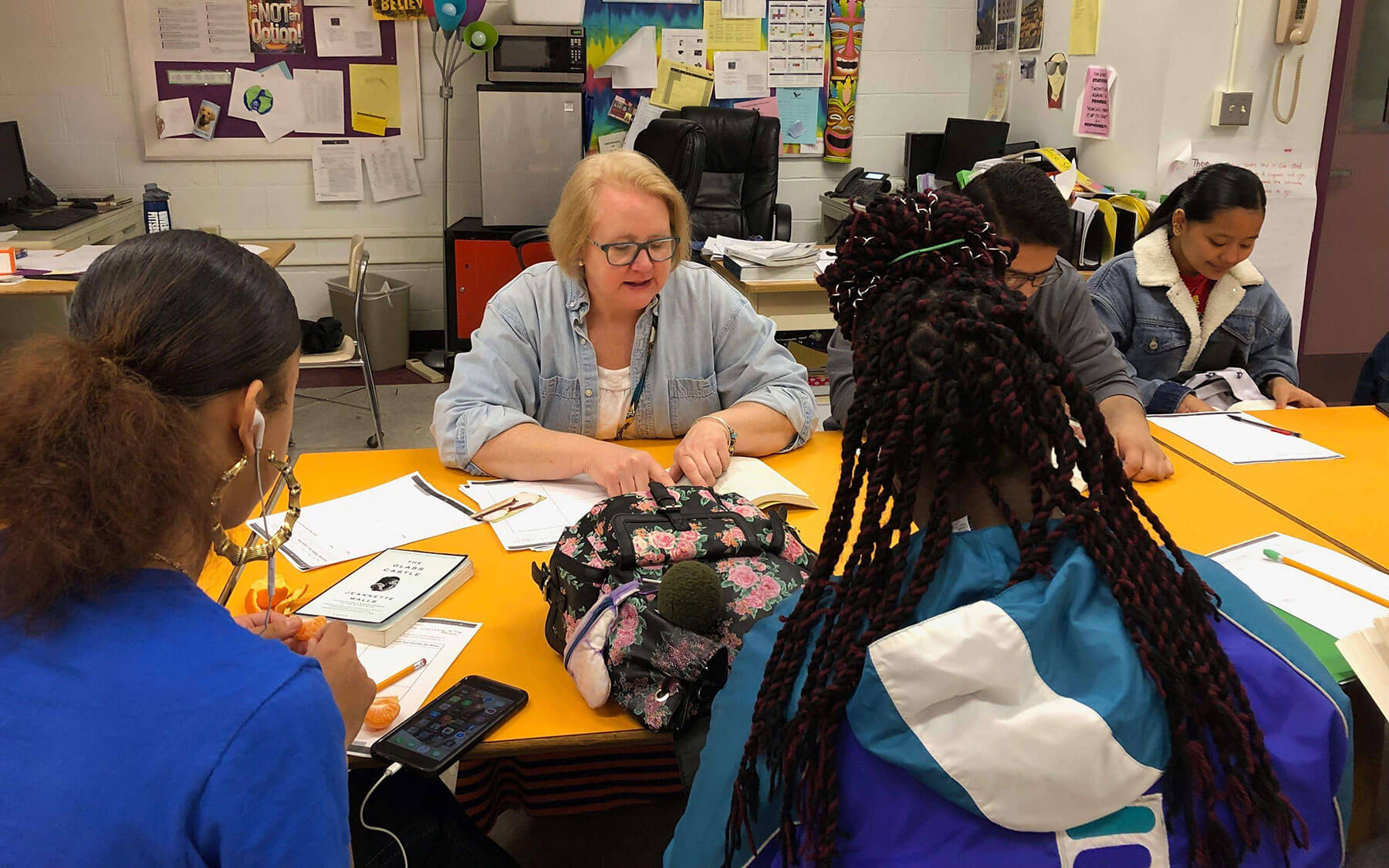

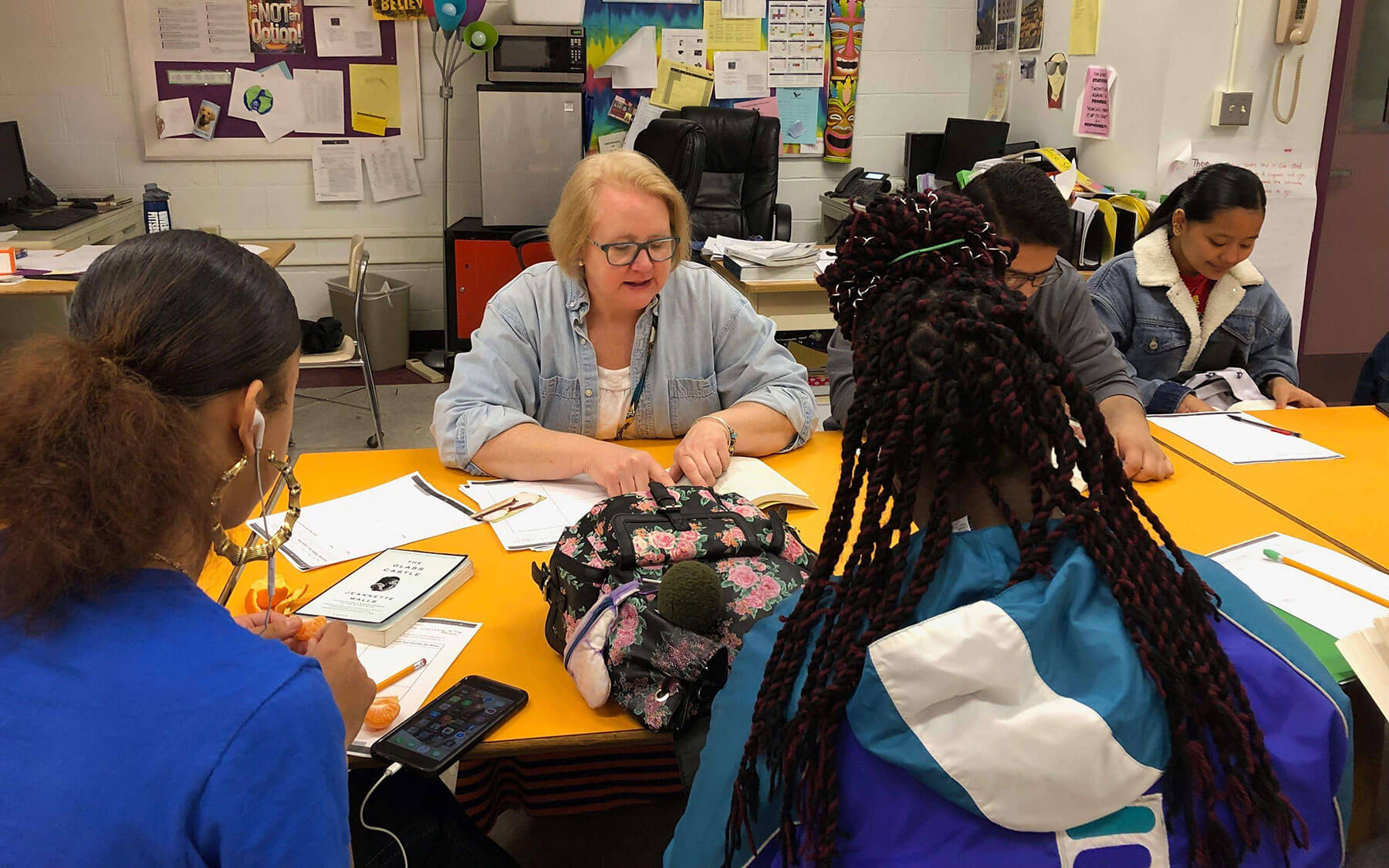

During an April general English class, teacher Cassidy Dunsmore, a traditional English teacher, co-taught with Christine Tapu, an ESL teacher.

The class was divided into two groups, with half working with Dunsmore on assessments and the others discussing a passage from the “The Glass Castle,” a memoir by Jeannette Walls about growing up in poverty with dysfunctional parents. Tapu read aloud about characters in the book being told to dump garbage in a hole they thought they were digging as a foundation for a new home.

She stopped often to ask students if they understood certain words and phrases.

“What does it mean to ‘break ground,’” she questioned. “What does the word gumption mean?” she later asked.

Brashear Principal Kimberly Safran said team teaching helps regular education teachers develop empathy for ESL students.

“You have to have so much patience. You also learn how hard it is for people who don’t speak the language. How hard it is to navigate the systems,” Safran said. “Teachers have to identify and battle their own implicit biases and learn about the various cultures and religions.”

Teachers are trained on working with students across cultures by the district’s equity office and Jewish Family and Community Services, which helps to resettle refugee families to Pittsburgh.

Safran said she’s seen the ESL population at her school grow to its current level from 40 students when she arrived in 2011.

“I love it. I think it’s good for our school and community because the students are exposed to so many different cultures and religions,” she said.

In April, students and staff celebrated diversity with Brashear Heritage Day. The library filled with students manning tables with information, artifacts and traditions from their native countries to share with classmates.

The first table represented Russia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and was manned by Oydin Ruzimukhamedova, 17, and Yulduzkhon Turdikulova, 16. They displayed Matryoshka dolls, which are ornamental stacking dolls. There was also a plate of candy from Uzbekistan and a quiz to match Russian words with English words.

At the African table, a poster corrected what students said is a common misconception: “Africa is a Continent not a country. Africa is made up of 54 different countries.”

“A lot of people think Africa is a country but there are lots of countries and religions. Every religion is different,” said Sarah Mugenyi, 20, then a senior. She has been in Pittsburgh for three years.

Students of all cultures jumped in to dance with the African students and others lined up to get their faces painted in the tradition of the Maasai tribe.

Jeovani Castano, 17, a senior, was manning a booth explaining the traditions of his native Mexico, including the celebration of the Day of the Dead.

When Jeovani first came to Pittsburgh five years ago, he felt as if he and his brother and sister “were the only three Latinos” in the district.

“The first month it was really hard,” he said of his start at South Hills Middle School. “The first year was the hardest but then I got to know people. They learned more about us.”

Mary Niederberger covers education for PublicSource. She can be reached at 412-515-0064 or mary@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Varshini Chellapilla.

Web design and development by Natasha Vicens.

This story has been made possible with the generous support of The Grable Foundation.