Data: Stats you should know about climate change in the Pittsburgh area

Sept. 19, 2019

(Graphic by Natasha Vicens/PublicSource)

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story. Read PublicSource's stories here.

Weather

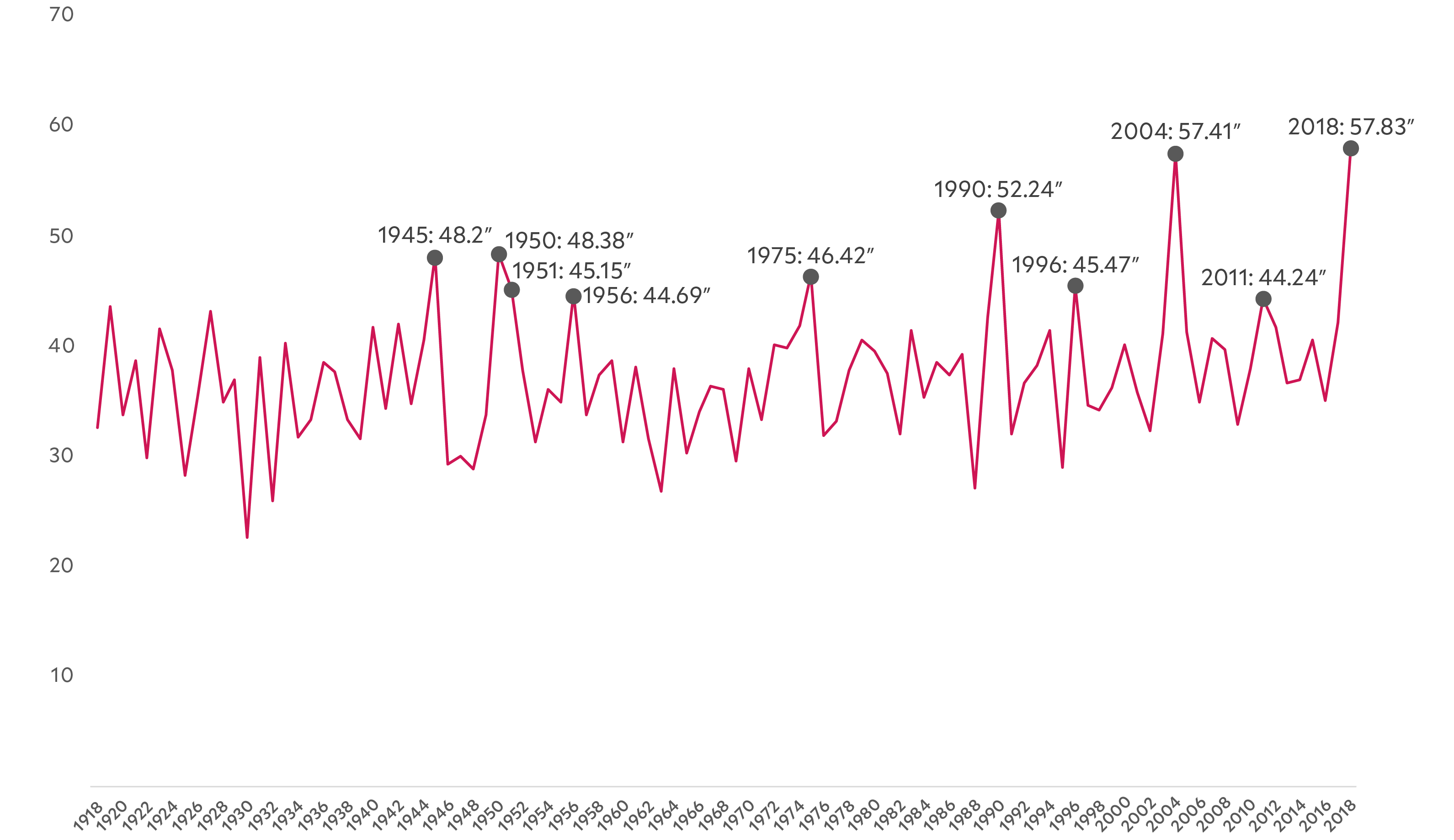

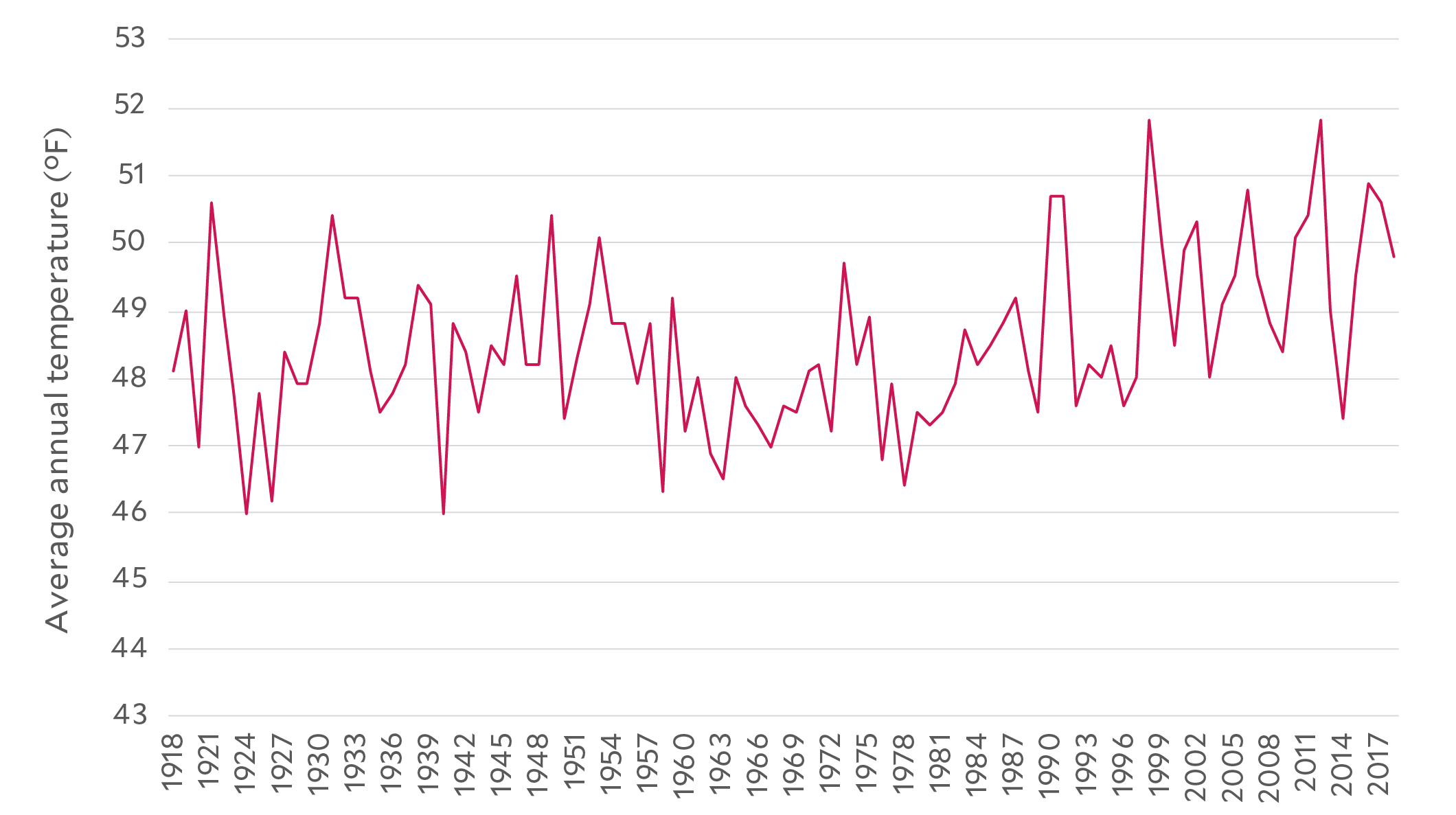

The Earth is warming, and so is Pittsburgh. The state of Pennsylvania has warmed about a half a degree Fahrenheit in the last century and has experienced more heavy rainstorms.

Average annual temperature in Pennsylvania

The Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection [DEP] predicts the conditions will increase flooding in the winter and spring, as we experience more intense rainfall, and droughts in the summer and fall, as the snow evaporates earlier due to warmer temperatures. A 2017 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report on climate-change impacts to the Ohio River basin predicts precipitation and stream flows will significantly speed up around 2040, which would likely lead to increased flooding, altered aquatic life and stress on the region’s reservoirs, dams and infrastructure. Another study in the journal Nature Communications predicts that Pittsburgh’s climate in 2080 would be most comparable to that of Jonesboro, Arkansas, which is about 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer with drier summers and wetter winters.

Last year, Pittsburgh experienced its wettest year on record. Increased precipitation has wreaked havoc across the city with flooding and landslides among the effects. After the city far exceeded its budget last year for landslide mitigation and remediation, Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto more than doubled funds for 2019 to $6.8 million. Aging infrastructure, such as the combined sewer overflow system, makes the more extreme weather a challenge the city will have to face.

Insects

The rise of the blacklegged tick population in Pennsylvania, a main culprit of the spread of Lyme disease in the state, can be correlated with climate change among a number of other factors, according to a recent Penn State study. Pennsylvania has one of the highest Lyme disease incidence rates in the country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Warmer weather and milder winters mean that ticks become active earlier and survive longer, allowing more time for the disease to spread.

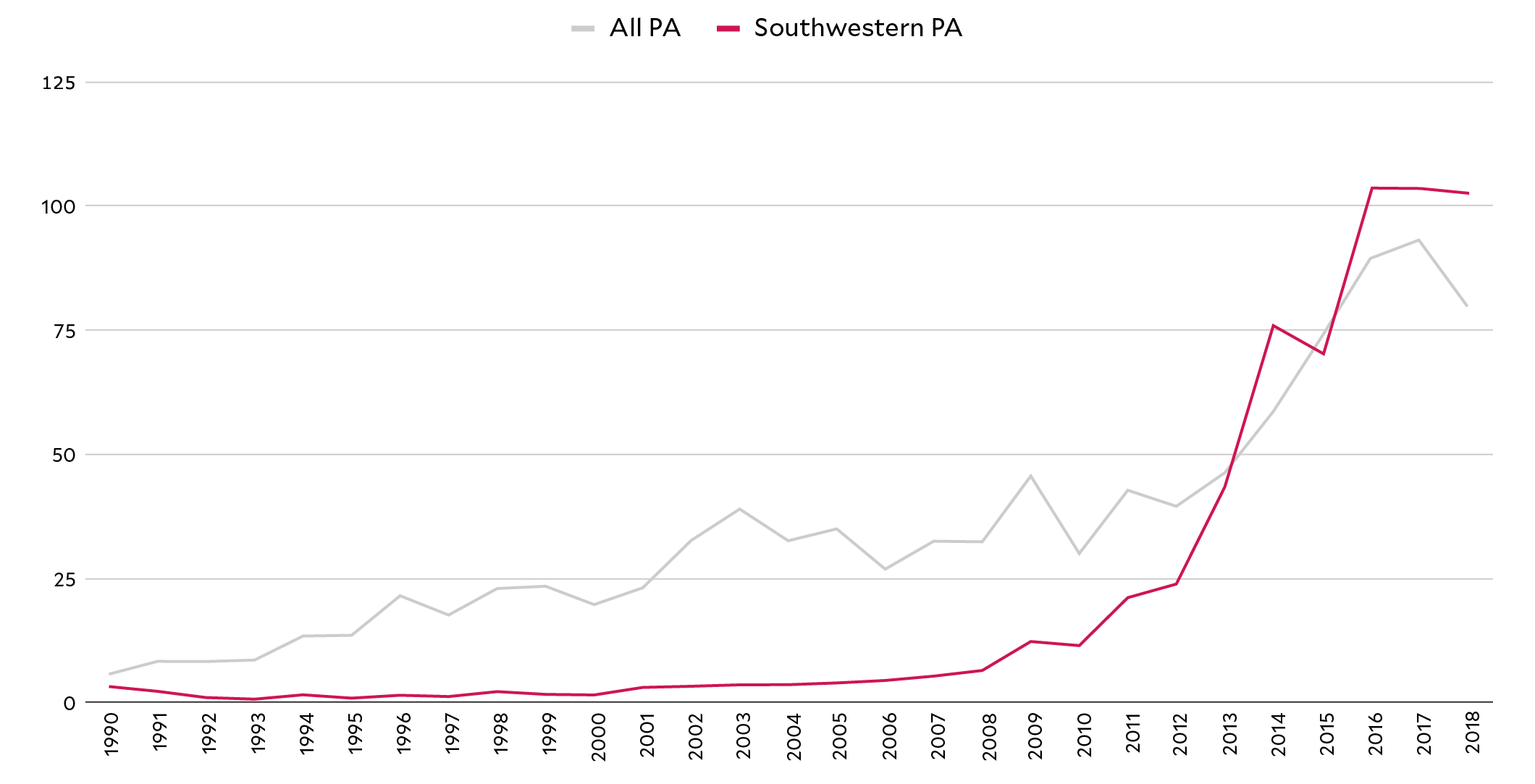

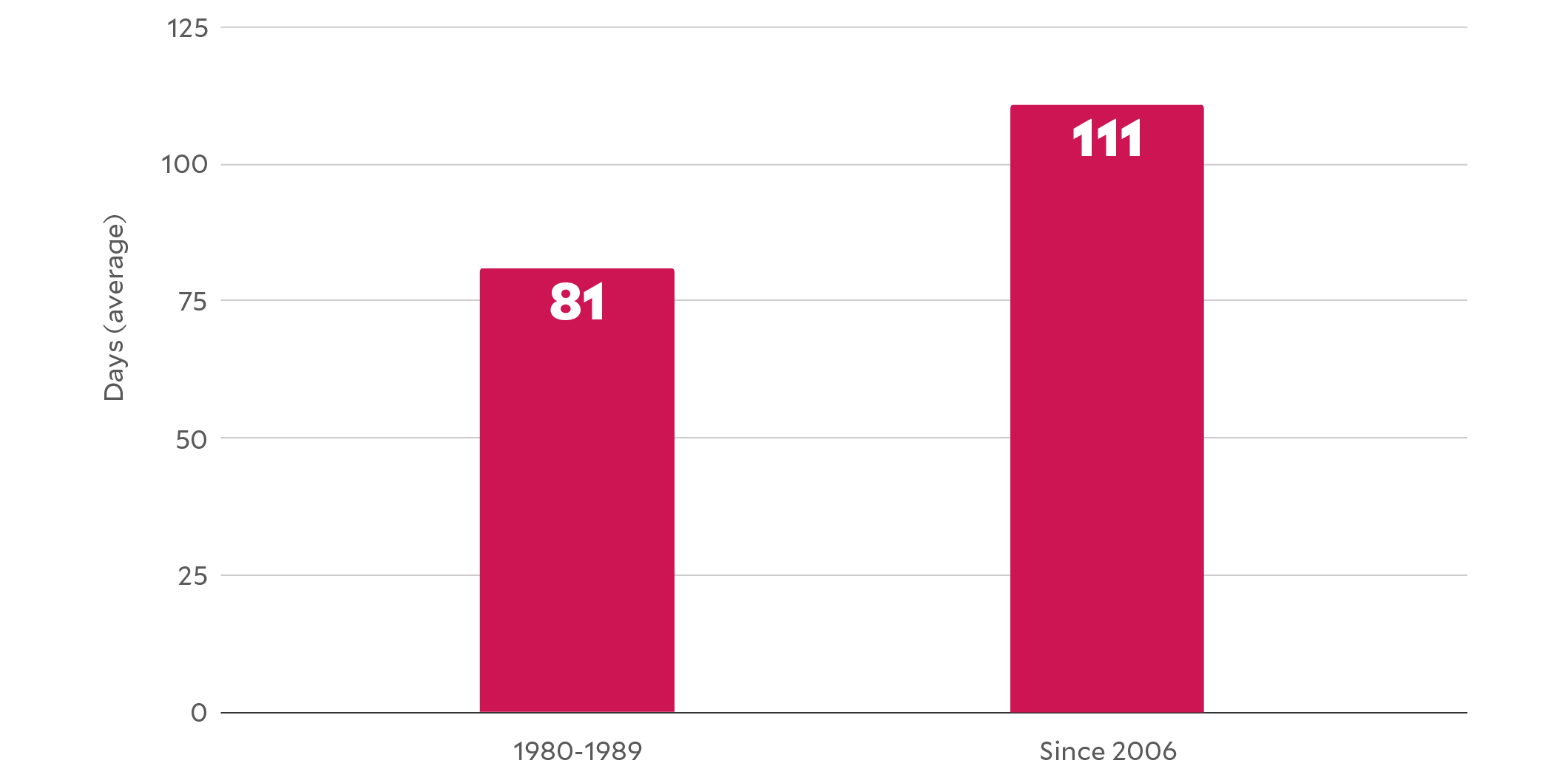

Out of the 200 largest metro areas in the United States, Pittsburgh is one of 10 cities that have experienced an increase of 30 or more days in their mosquito seasons since 1980, according to a study by Climate Central, a group of scientists and journalists reporting on climate change impacts. Longer mosquito seasons mean more opportunity for diseases — such as the West Nile virus — to spread.

BUILDINGS

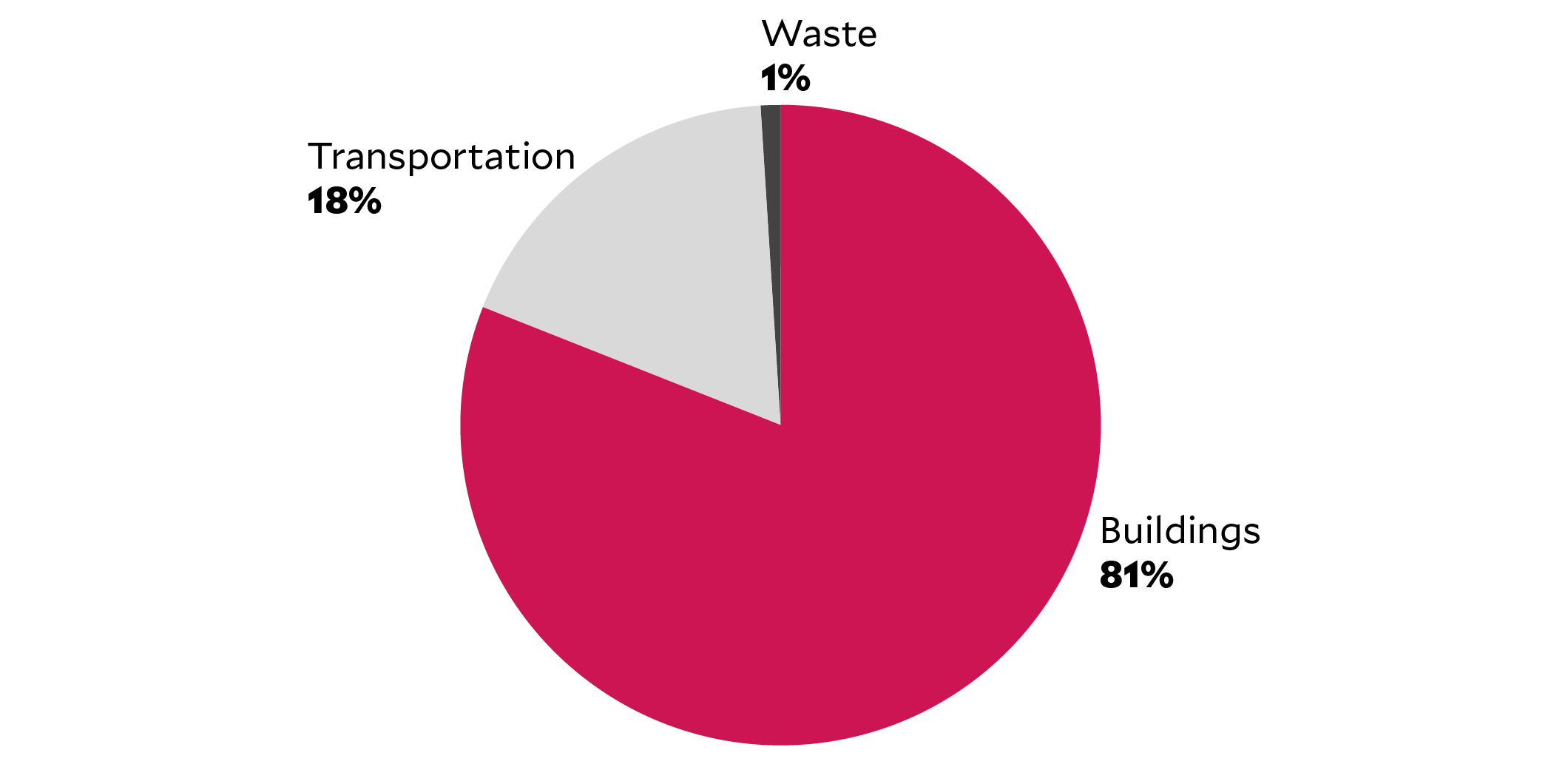

The City of Pittsburgh is targeting emissions from buildings in its effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 50% by 2030.

Buildings create 81% of Pittsburgh’s greenhouse gas emissions.

While the majority of these emissions are generated from electricity use and natural gas consumption in commercial buildings, residential properties account for a quarter of the city’s overall greenhouse gas emissions. The majority of Pittsburgh homes were built before 1960 before energy-efficiency standards were in place. Read more in the city’s climate action plan and a PublicSource story on reducing building emissions.

*Note: Data in Pittsburgh’s climate action plan is largely based on 2013 data because the city does a greenhouse gas inventory every five years, according to Sarah Yeager, the city’s energy planner. The city is working to update the plan with 2018 data.

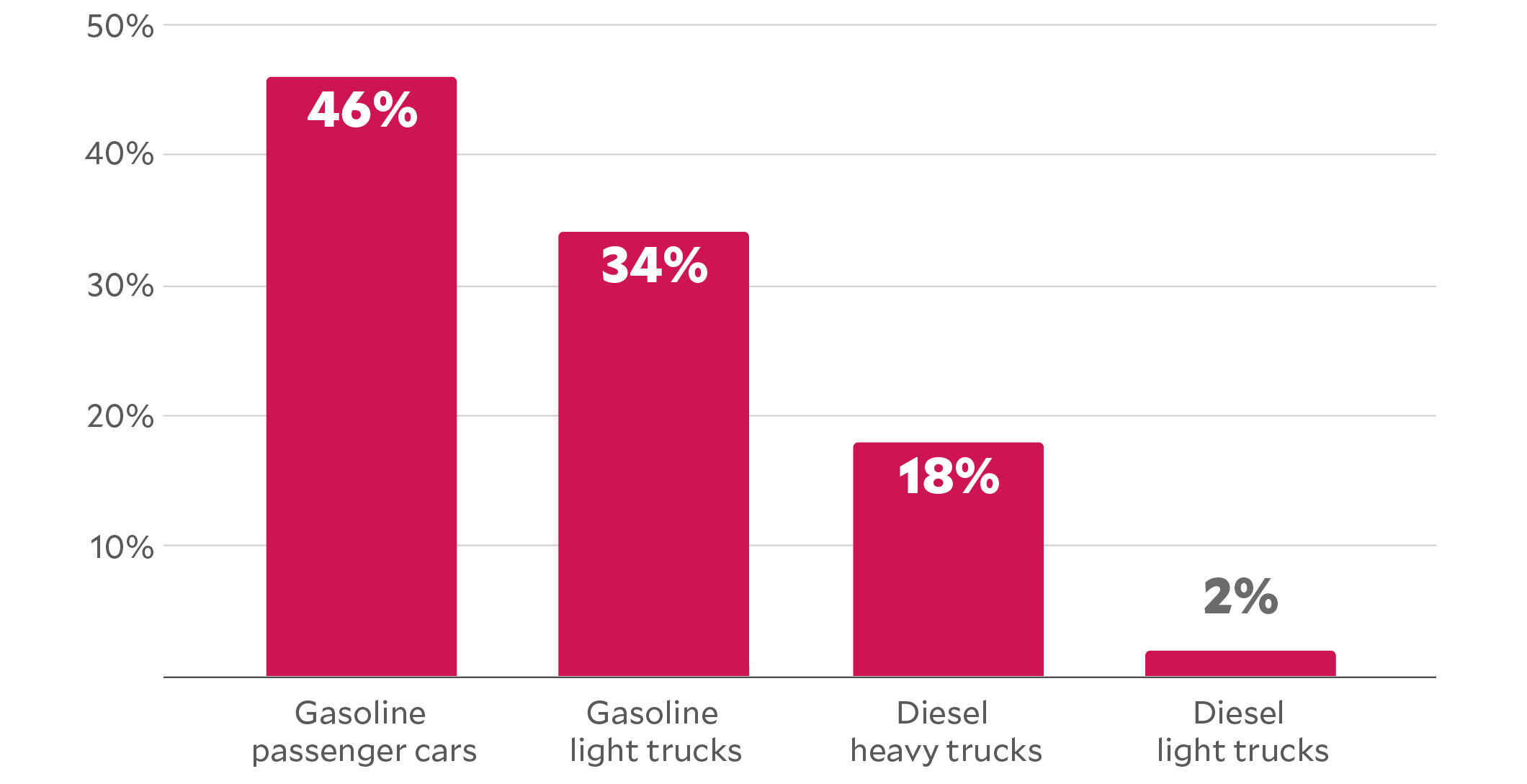

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation-related emissions make up about 18% of Pittsburgh’s overall emissions output. The largest contributor to transportation-related emissions in the city are trips taken in single-occupancy cars. According to the city’s climate action plan, reducing such trips “will help reduce emissions, improve air quality, reduce infrastructure maintenance costs and reduce congestion throughout the City of Pittsburgh.” The city has related goals to build out an electric vehicle fleet and improve and maintain pedestrian and bike infrastructure.

TRANSPORTATION-RELATED EMISSIONS

IN PITTSBURGH (2013)

(Source: City of Pittsburgh climate action plan)

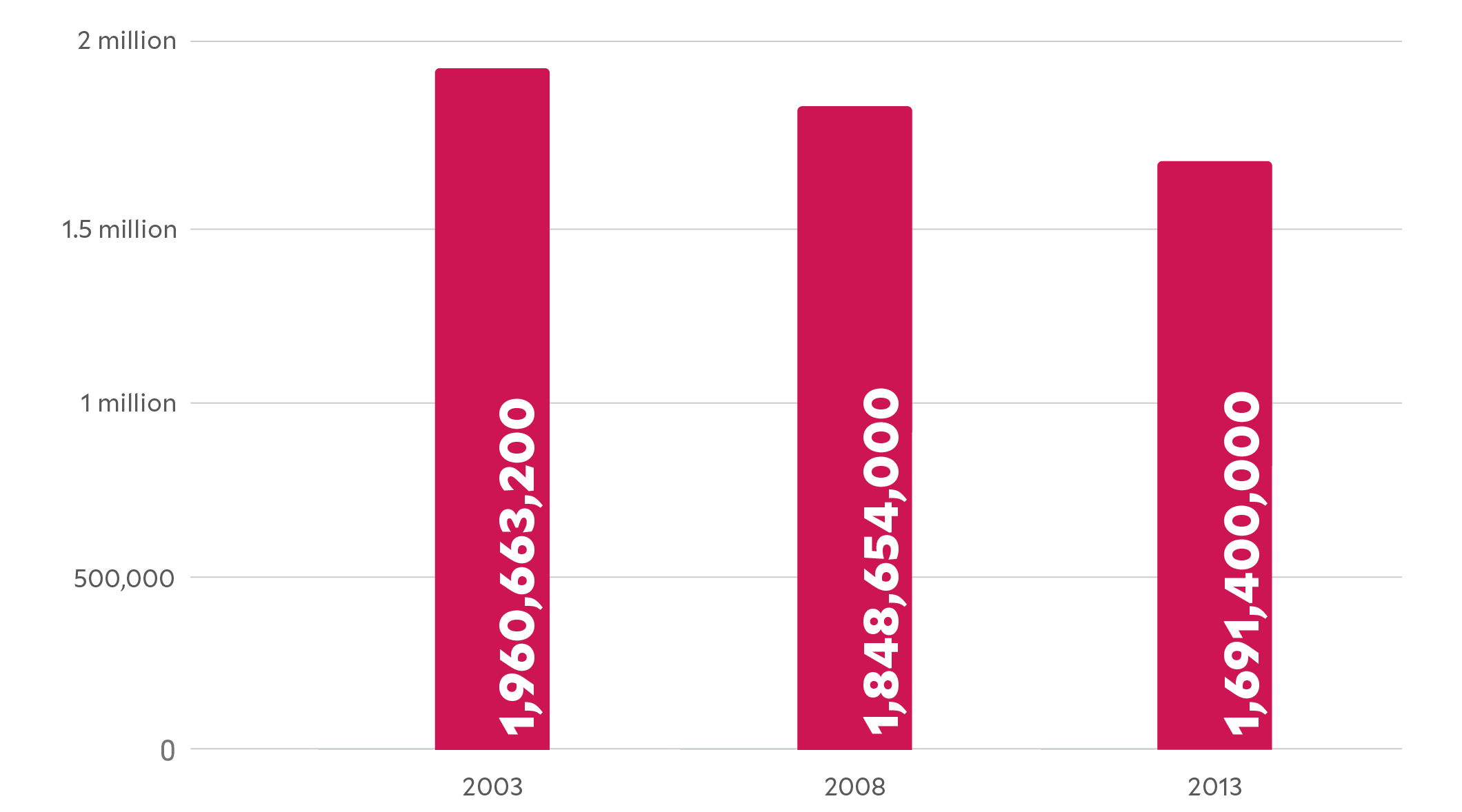

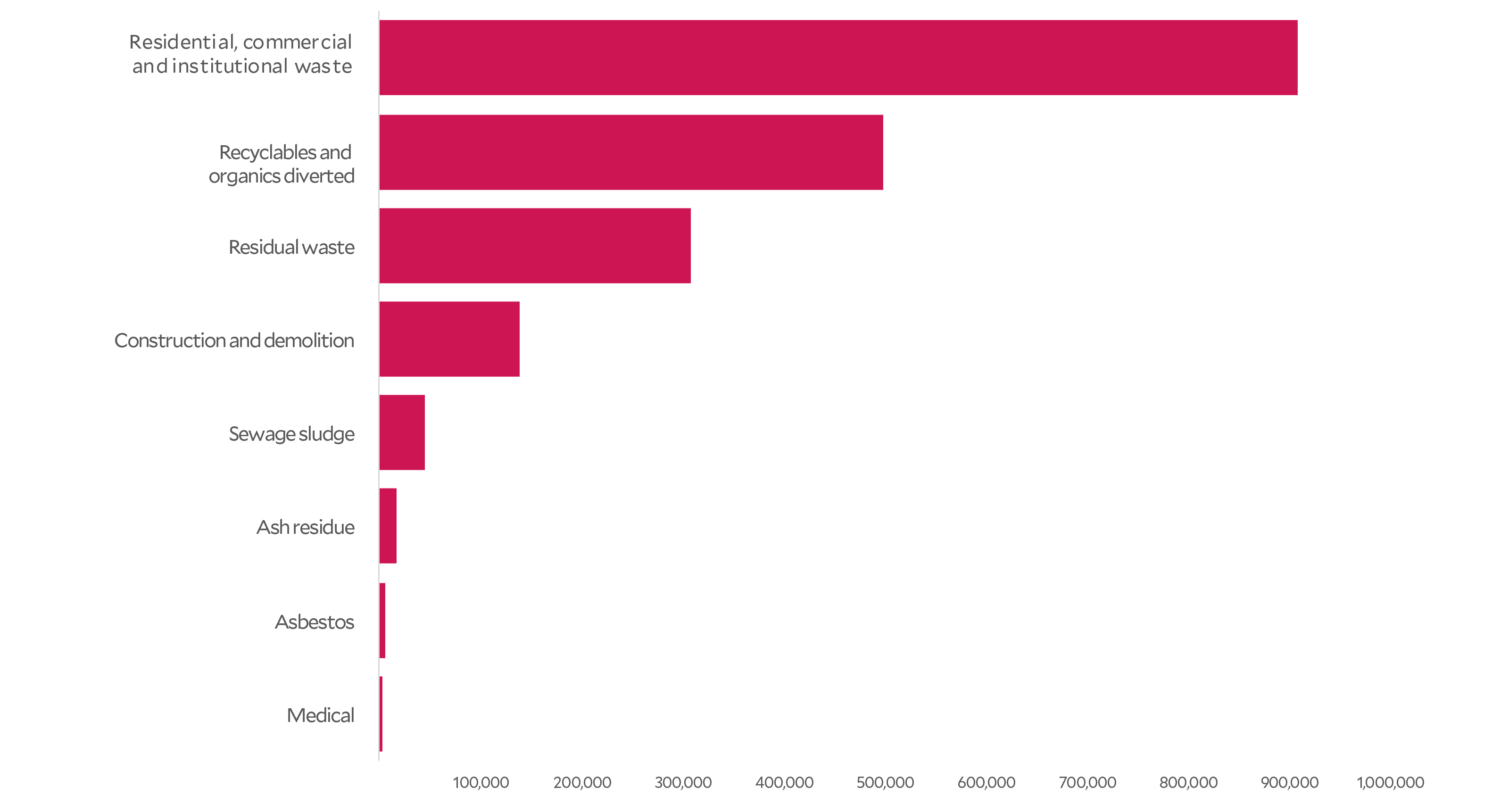

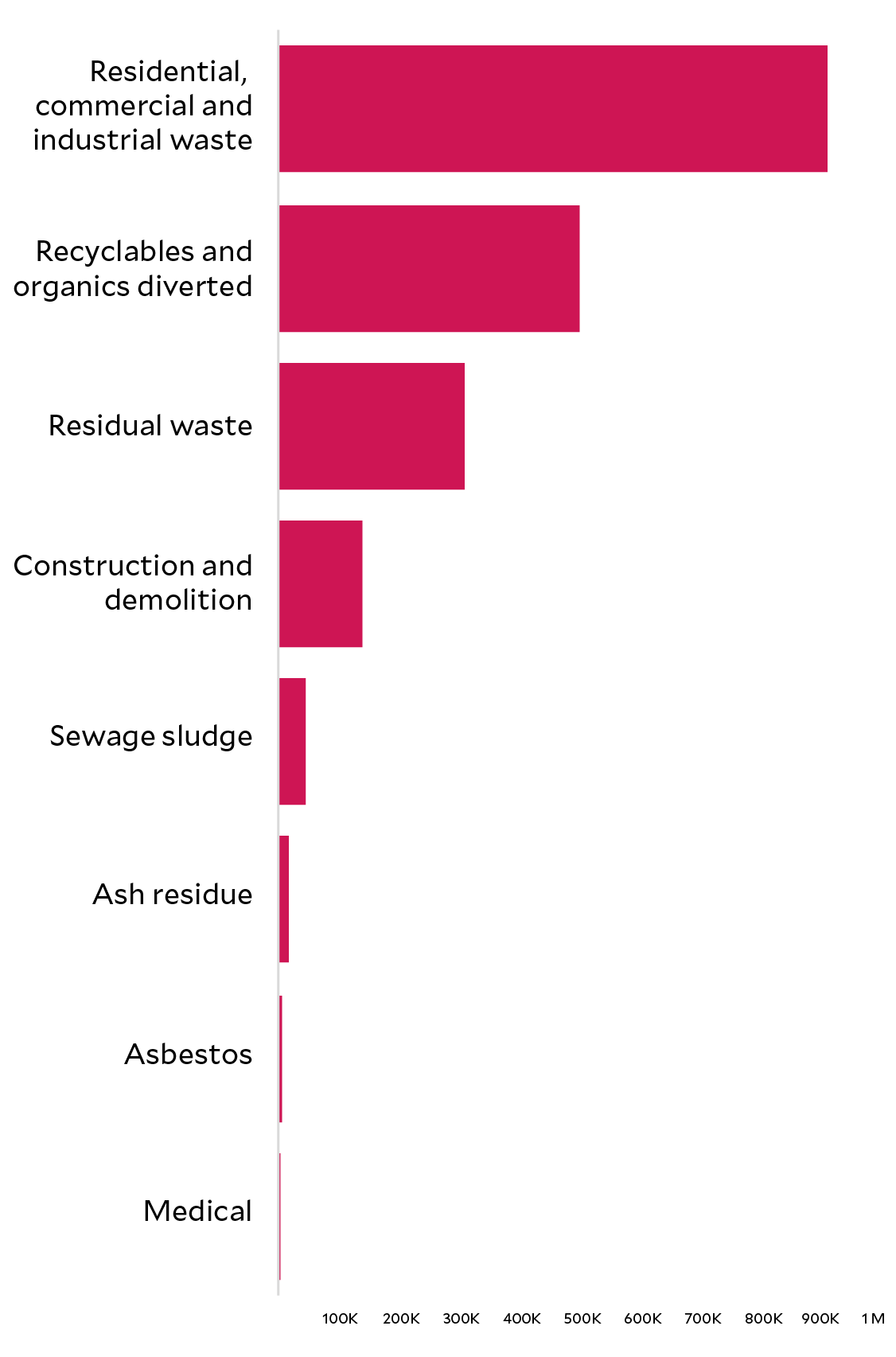

WASTE

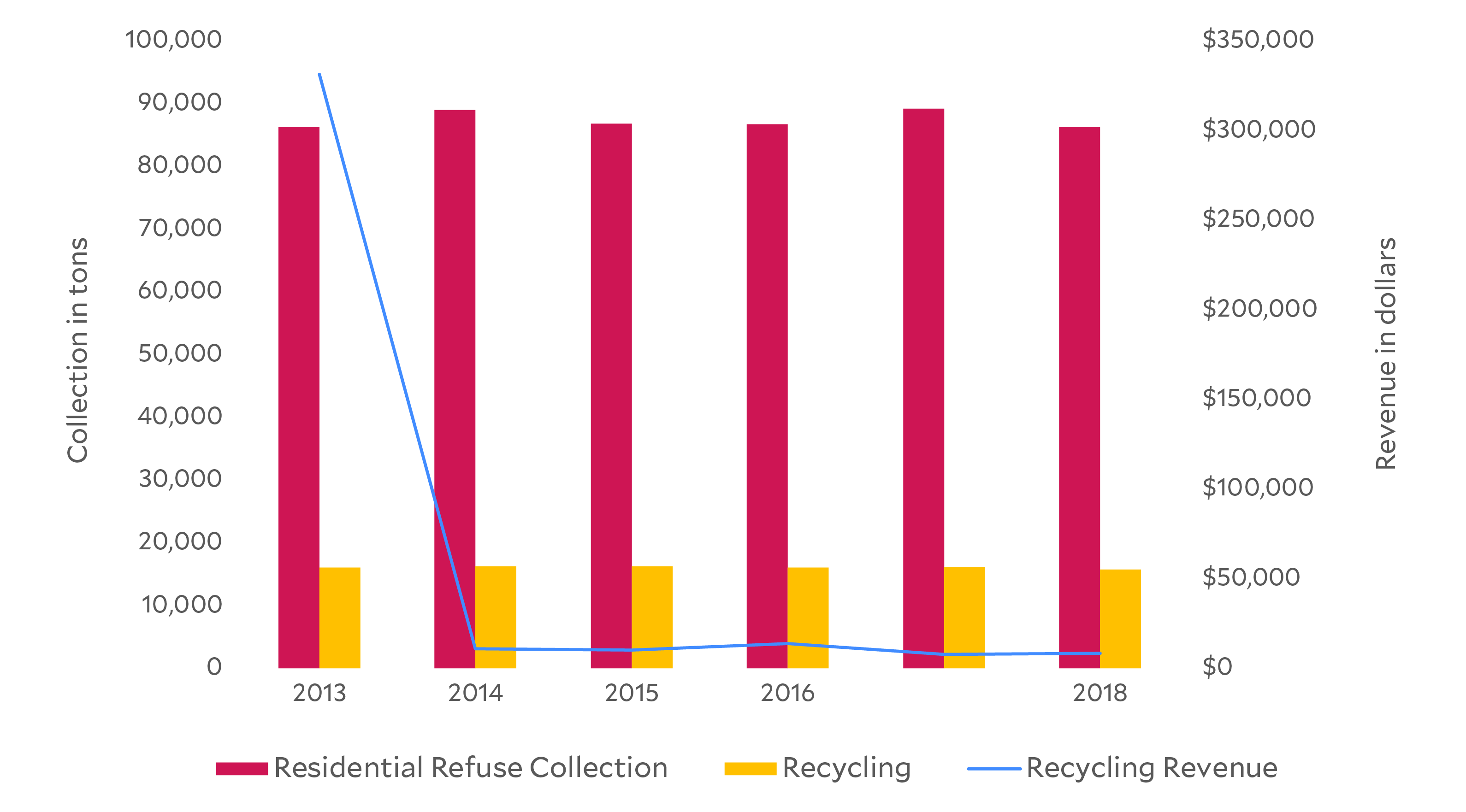

The City of Pittsburgh only collects trash from households with five or fewer units, meaning there is no available data on about a quarter of city households whose waste is hauled by private trash collectors. However, data from Allegheny County gives an idea of the percentage of waste discarded, recycled and composted as well as the volume of waste.

Emissions from city landfills constitute about 1% of the sector-based emissions the city calculates, but this model doesn’t take into account emissions from production, transportation and use of the waste, only the methane that the landfills themselves release as organic matter decomposes. Recycling has stayed at around the same level, but changing global regulations mean the city has seen an extreme drop in revenue.

PITTSBURGH RESIDENTIAL REFUSE AND

RECYCLING COLLECTION AND REVENUE

(Source: City of Pittsburgh 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report)

The city climate plan hopes to meet the goal of zero waste by 2030. First, the city is attempting to collect more data on what Pittsburgh is throwing away and is looking to expand distribution of recycling bins.

TREES

City of Pittsburgh's goal:

Plant 780,000 trees by 2030.

City of Pittsburgh's goal: Plant 780,000 trees by 2030.

Trees absorb carbon dioxide [CO2] in the air, then store the carbon and emit oxygen. This is called carbon sequestration. While Pittsburgh already has one of the highest percentages of tree cover in the country, city goals include planting new trees and preserving existing ones to help reduce Pittsburgh’s greenhouse gas emissions. The city’s goal is to actively plant 780,000 more trees by 2030, which would increase the tree cover from about 40% to 60%.

(Source: City of Pittsburgh climate action plan)

CRACKER PLANT

The Beaver County ethane cracker will emit

more than 2.2 million tons of CO2 annually.

The Beaver County ethane cracker will emit more than 2.2 million tons of CO2 annually.

Passenger vehicles release about 4.6 metric tons of CO2 a year, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]. The EPA provides a tool that compares emissions to the number of cars driven. The more than 2.2 million tons of CO2 Shell’s ethane plant would emit annually is equivalent to the emissions released from about 433,000 cars driven for a year.

It would take about 14% of Pennsylvania’s forests to absorb the more than 2.2 million tons of CO2 year, according to the Breathe Project, a Pittsburgh-based environmental advocacy group. The group wrote a letter in August along with 12 other Pittsburgh-area environmental groups asking President Donald Trump to stop supporting the ethane cracker.

Trump visited the plant’s construction site in August 2019 amid protests. The Beaver County plant will produce plastic parts used in many consumer goods and could make Western Pennsylvania a hub for the petrochemical industry.

(Source: Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection)

Natasha Vicens is PublicSource's interactives and design editor. She can be reached at natasha@publicsource.org.

Nora Mattson was a PublicSource data and reporting intern. She can be reached at nmattson@thetartan.org.

This story was fact-checked by Juliette Rihl.