10 big problems with policing, and approaches to addressing them

Oct. 15, 2020

(Photo illustration by Natasha Vicens/PublicSource)

The death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis officer didn’t just set off protests. It enlivened discussion about the future of policing, nationally and around Pittsburgh.

Renewed police-community tensions have flared on Mayor Bill Peduto’s home street, at the Squirrel Hill farmer’s market, in front of the East Liberty Target store, and in countless protests throughout the region.

The issues affect everyone, from grieving families to taxpayers.

The cost of federal court verdicts and settlements in 40 police use-of-force lawsuits within Allegheny County, since 2009, is poised to exceed $12 million, ultimately covered by taxpayers. Eight of those lawsuits stem from police-involved deaths of Antwon Rose II, Jennifer Piccini, Nicholas Haniotakis, Gary Beto, Lawrence A. Jones Jr., Mark Daniels, Christopher M. Thompkins and Bruce Kelley Jr.

A mayoral Community Task Force on Police Reform is expected to release its recommendations for Pittsburgh soon. Based on reporting by PublicSource and others, before and after Floyd’s death, here are 10 of the region’s policing problems, and approaches under consideration here, or tried elsewhere.

PROBLEM

1. Not mayors, not chiefs, but arbitrators decide police discipline

Mayors and police chiefs can fire, suspend or otherwise discipline officers who break the rules — but may end up having to put them back on the beat if an arbitrator rules that the dismissal violated the terms of the officer’s union contract. In Pennsylvania, police discipline can, and often is, governed by collective bargaining and contract arbitration. Peduto says that thwarts efforts to change the policing culture. Union leaders argue that this is an important protection for officers and a bulwark against politicization of law enforcement.

Excerpt from the arbitration award of Jan. 9, 2020, resolving the contract dispute between the City of Pittsburgh and the Fraternal Order of Police Fort Pitt Lodge 1.

In Pittsburgh, the Fraternal Order of Police is even now wrestling with the city, in a Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board [PLRB] case, over changes the city made in the procedures that govern investigations into officers’ use of force.ction for officers and a bulwark against politicization of law enforcement.

Another approach: A matrix, instead of arbitration

Peduto has argued that state Act 111 — which governs contract disputes between municipalities and their police and firefighters unions — should be amended to remove discipline from the bargaining and arbitration process.

What then? Some departments (recently including New York City’s) have adopted police disciplinary matrices that outline the consequences for a variety of types of misconduct and can factor in the severity of the wrongdoing and the officer’s history.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

2. If officers rack up complaints, the public may not know

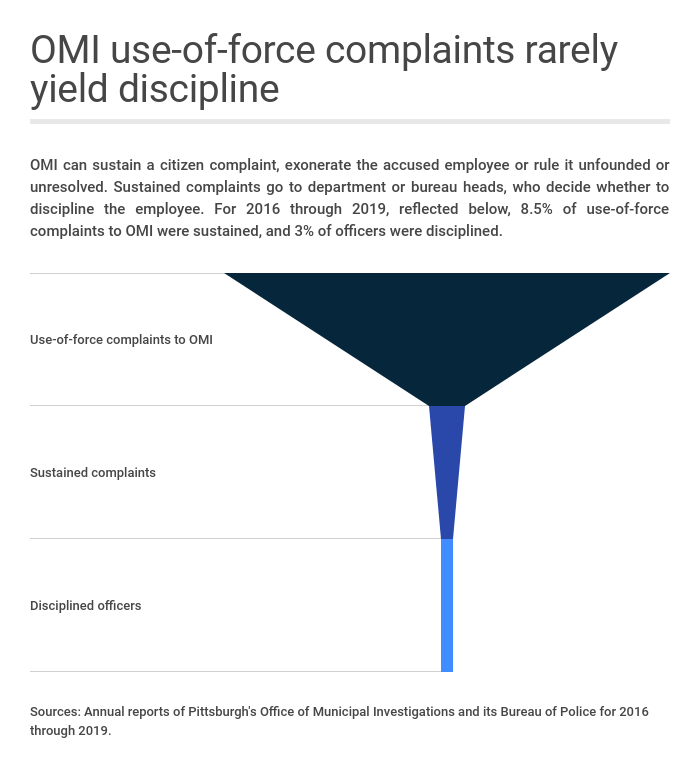

The Office of Municipal Investigations, the city’s internal affairs unit, releases only annual reports which don’t reveal whether there are blatant, repeat offenders in the ranks. The reports don't provide enough detail to evaluate a system of investigation and discipline in which 549 forceful arrests coincided with just 27 use-of-force complaints to OMI and one officer punished (with an oral reprimand) for excessive force last year.

A new state law allows police departments to see the history of complaints against an officer who is applying for a job. But the act exempts such records from the Right-to-Know Law. In fact, if an officer is “adversely affected by the release of employment information,” they can sue the municipality and recover punitive damages. That means the public has little means of learning whether a department’s officers are racking up scores of complaints with impunity.

Another approach: Release de-identified data about accusations against police

Some cities in other states make information on complaints against police readily available. Minneapolis, for instance, has a detailed online dashboard that allows the public to easily search up the number of complaints, and the resulting discipline, against any officer on the force.

While Pennsylvania law might not allow municipalities to release complaint histories of officers by name, Philadelphia manages some measure of transparency. That city releases data that doesn’t name officers or complainants, but nonetheless includes “demographic details of the police officer involved, the allegations, and the status of the PPD's Internal Affairs Division's investigation of and findings (if available) about the allegation.”

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

3. Civilian review of policing is criticized as ineffective

Remember the brawl at Kopy’s bar between Pagans motorcycle gang members and Pittsburgh undercover detectives? The Oct. 12, 2018 incident was a topic at the Sept. 22, 2020 meeting of Pittsburgh’s Citizen Police Review Board. CPRB Executive Director Elizabeth Pittinger told the board that since the district attorney didn’t criminally charge the involved officers, and the police chief didn’t discipline them, there might be little for her agency to do. Board members discussed the possibility of a public hearing, and Pittinger says it’s coming soon, but two years after the incident, the CPRB still hasn’t taken action.

In Allegheny County’s suburbs, meanwhile, there is no system of civil review of police misconduct complaints.

Another approach: A stronger city board, and a new county board

A referendum question on the ballot in November will ask voters whether the city should compel officers to cooperate with CPRB’s investigations. The referendum would also require the police chief and mayor to review CPRB’s recommendations before making final determinations regarding discipline. If it passes, it could still face legal challenges if it conflicts with the city's contract with the police union.

Allegheny County could also get a civilian review board of its own — though efforts to establish one over the past two years have not yet been successful. A bill to create such a board was first introduced to Allegheny County Council in 2018. After failing in a 2019 vote, it was reintroduced in January and remains in committee.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

4. Suburban police budgets and procedures are uneven

While the city has recently been the site of protests, the deaths of Rose, Piccini, Beto and Kelly, all at the hands of police outside the city over the last decade, show that the use of deadly force is a countywide controversy. Rose’s death, especially, led to scrutiny of the wildly uneven pay, training and accountability among the county’s 100-plus police departments.

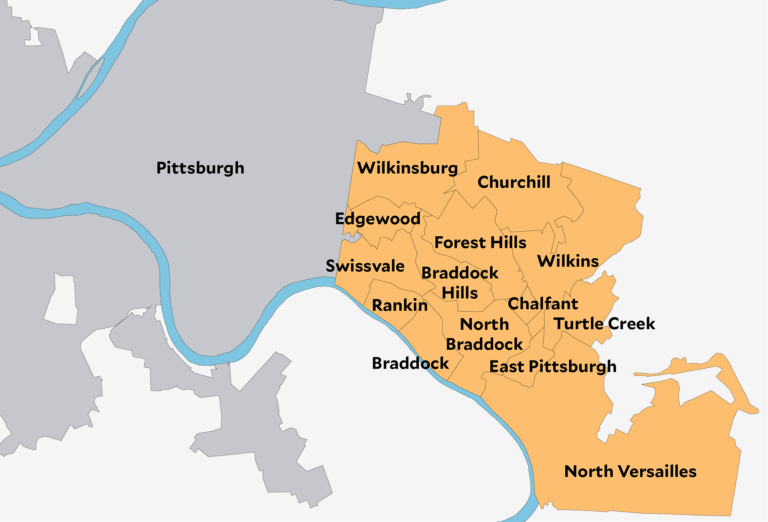

The Mon Valley epitomizes Allegheny County’s fragmented policing structure. Most boroughs and townships have their own departments, while East Pittsburgh is policed by the state, and Forest Hills covers Chalfant.

Another approach: Merge small departments

Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald is cheerleading long-running efforts to create one department to police East Pittsburgh, Braddock, North Braddock and Rankin. The first is now policed by state troopers, while the other three have small departments staffed mostly with part-time officers.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

5. A badge may not solve a behavioral health crisis

Three of the deaths listed above (Piccini’s, Beto’s and Kelly’s) stemmed from police handling of incidents that appeared to start with mental or behavioral health problems, rather than any intent to engage in violent crime, according to lawsuits filed by their families. While Allegheny County offers Crisis Intervention Training to police, it’s far from universal and doesn’t always keep mental health outbursts from turning tragic.

Another approach: Address mental health problems with medical and social services

Pittsburgh is already working to expand a North Side-based effort to keep troubled youth out of jail. The Allegheny County Health Department is funding a Congress of Neighboring Communities effort to take the concept of Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (from the criminal justice system, to the social service system) to the suburbs. And it looks like the county may be preparing to do more to better address behavioral crises.

In August, Peduto told PublicSource his team has been looking into a mobile crisis intervention program that has been hailed by police reform advocates as an effective alternative to addressing nonviolent 911 calls. In Eugene, Oregon, an emergency response team called CAHOOTS works with police to respond to calls involving mental illness, homelessness and addiction. CAHOOTS workers are unarmed and trained in de-escalation and crisis intervention. According to CAHOOTS, its workers answered 17% of the Eugene Police Department’s calls in 2019 and save the city roughly $8.5 million per year.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

6. Traffic stops too often spiral out of control

In 2015, Pittsburgh police saw a Black man driving, and an officer referred to him insultingly and wondered if he was “lost or something.” The officer’s partner concluded he was “scared,” and they decided to stop him “just on principle.” That stop turned into a high-speed chase, at the end of which a 12-year-old girl was severely injured. The city has agreed to a $392,000 settlement in the resulting lawsuit. (Settlements are typically not admissions of wrongdoing.)

Excerpt from a motion filed by the plaintiff’s attorney, Alexander Wright, in a civil lawsuit in federal court alleging injuries to a 12-year-old at the end of a high-speed chase by Pittsburgh police that started with a traffic stop.

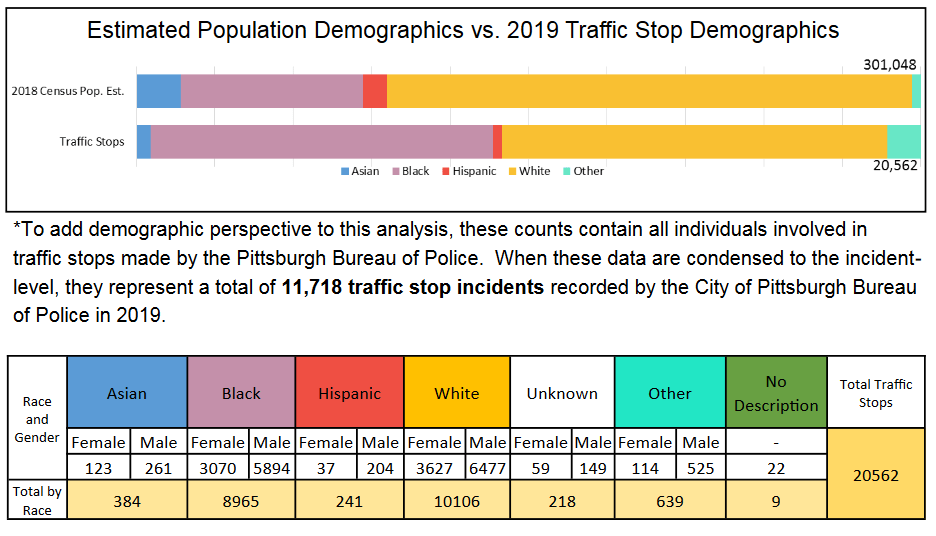

Black residents may be more likely to dread encounters with police, and in Pittsburgh, they are statistically more likely to face traffic stops. Last year the percentage of Pittsburgh traffic stops involving Black drivers easily outstripped the Black share of the population, according to the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police annual report. The same was true in 2018 and 2017.

Charts from the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police 2019 annual report show that Blacks are more likely to be pulled over than whites.

Another approach: Shift traffic duties to unarmed civilians

One U.S. city is moving forward with removing police from traffic stops altogether. Lawmakers in Berkeley, Calif., approved a plan in July that would shift the responsibility from police to unarmed city employees.

The plan, which is believed to be the first of its kind, calls on the city to create a Department of Transportation to enforce traffic laws and parking rules independently from law enforcement.

Officials in Montgomery County, Maryland, are considering a similar approach — though they must first overcome the hurdle of Maryland state law, which says only sworn officers may enforce traffic law.

Pittsburgh City Councilperson Erika Strassburger told PublicSource in August that she is interested in exploring removing police from traffic stops.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

7. Surprise tactics can escalate situations

Portland made national news in mid-July when federal law enforcement officers began pulling protesters into unmarked vehicles. A month later Pittsburgh followed suit, when plainclothes police jumped out of an unmarked van and apprehended a protester. The tactic, which was captured in a viral video, prompted public outcry and questions about its constitutionality, and Peduto said it would no longer be used against peaceful protesters.

Another approach: Limit, or ban, plainclothes police

In June, New York City’s police department made a move that its commissioner, Dermot F. Shea, called a “seismic shift” in culture: disbanding many of its plainclothes units. According to the New York Times, Shea said the units were involved in a disproportionate number of civilian complaints and fatal shootings by police.

In 2017, then-Baltimore police Commissioner Kevin Davis announced the end of plainclothes policing in the city altogether. The decision came after seven officers were federally indicted for stealing drugs, guns and money. “I want you to look like a cop, because I can’t ask you to act like a cop unless you look like one,” Davis told the New York Times. (Plainclothes officers are different from undercover officers. While undercover officers adopt a false identity, officers in plainclothes typically wear their badge visibly and may have other identifying markers, like a bulletproof vest.)

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

8. Black youth are treated like criminals in schools

As in many places in the U.S., Black youth in Allegheny County have been consistently overcriminalized by police, schools and the criminal justice system at large. A September report by the Black Girls Equity Alliance found that Black girls in Allegheny County are 10 times more likely to be referred to the juvenile justice system than white girls, and Black boys are seven times more likely to be referred than white boys.

Another approach: Remove police from schools

Since the death of George Floyd, several U.S. cities — including Minneapolis, Denver and Portland — moved to cut ties with police, citing the criminalization of students of color and a need to reevaluate their relationships with local police departments. In June, parents, activists and advocacy groups called on Pittsburgh Public Schools to do the same.

Kimberly Booth, assistant chief probation officer in the Allegheny County Juvenile Probation Office, named two possible reforms: a moratorium on summary citations in schools, and reallocating funds used for school police toward mental health counseling.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

9. The policing budget is vast, and not fully disclosed

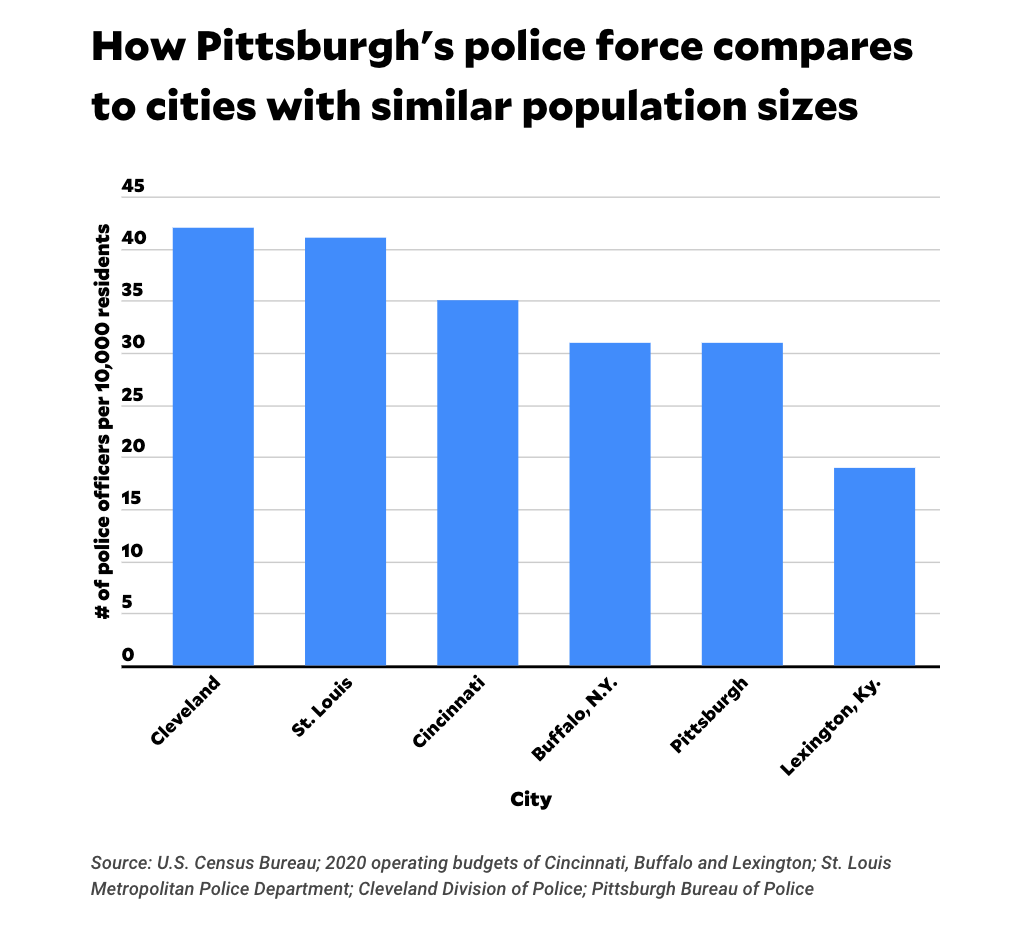

The Pittsburgh Bureau of Police operating budget is $115 million this year. That’s a little less than a fifth of the city’s overall operating budget, which experts told PublicSource is “on the light side.”

But that doesn’t account for all of the money the city spends on policing. The city’s capital budget, which funds major projects like new construction or repairs to existing facilities, includes other policing and public safety costs. Big ticket items in this year’s budget include $2.7 million for the relocation of the Zone 5 police station, $950,000 for upgrades to the Zone 4 station, $600,000 toward a new public safety training facility and $450,000 for security camera replacements and maintenance. The budget also allotted $376,000 to the Equipment Leasing Authority to purchase 16 police patrol motorcycles.

Another approach: Provide a comprehensive police budget — and further involve the community in the decision-making process.

Activists and lawmakers PublicSource spoke with called on the city to provide a comprehensive breakdown of its police spending and to make sure residents are included in the budget creation process.

Some cities provide a more detailed breakdown of police spending in their budgets. Buffalo’s police budget has line items for vehicles ($675,000), wages for time spent in court ($3.1 million) and a “perfect attendance incentive” ($838,000). It even includes the number of 911 calls, arrests and cases solved that year. Still, it’s not a complete picture: its police operating budget does not list capital improvement projects, officer healthcare or pensions.

↑ Back to topPROBLEM

10. Concerned citizens take a back seat in police policymaking

In June, while the image of George Floyd’s death was still fresh, a new Allegheny County Black Activist/Organizer Collective issued a dozen demands to Peduto and Fitzgerald, ranging from the removal of police from schools to the end of no-knock warrants and cash bail. Peduto then created a Community Task Force on Police Reform, and Fitzgerald’s administration later quietly launched an Allegheny County Crisis Response Stakeholder Group.

Peduto’s panel initially included one member of the activist/organizer collective, Brandi Fisher, but she dropped out. The county panel, as initially constituted, included members of three community organizations, but no established police accountability advocates.

Another approach: Get civilians involved in police policy long-term

In Los Angeles, police policy isn’t set by a chief or a mayor. It’s set by five commissioners, all civilians, who meet weekly and publicly. It’s now led by a former federal prosecutor but includes one social justice activist and an advocate for community-based organizations.

Since 2017, Seattle has had an inspector general, picked by a search committee and approved by the city council. Lisa Judge, the city’s current IG, is a lawyer with experience working with police departments, but is not a current or former cop. Not only does she audit the department’s performance, review complaints and suggest policy improvements, but she has “unfettered access,” per the city website, including at the scene of use-of-force incidents.

Similarly, Denver has, since 2005, an Office of the Independent Monitor, also headed by a civilian. That office in June agreed to investigate the Denver Police Department's use of force in addressing the protests that followed Floyd's death, a process which the city's Department of Public Safety had reportedly committed to support.

↑ Back to topRich Lord is PublicSource’s economic development reporter. He can be reached at rich@publicsource.org or on Twitter at @richelord.

Juliette Rihl is a reporter for PublicSource. She can be reached at juliette@publicsource.org or on Twitter at @julietterihl.

This story was fact-checked by Amanda Hernandez.